The Cold War

About 20 years ago, I picked up a book entitled The 50-Year Wound: How America's Cold War Victory Has Shaped Our World, by Derek Leebaert. This book was published in 2003, a decade or so after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Enough time had elapsed for knowledgeable observers to begin to put the Cold War into context and assess what the post-Cold War international world order would look like.

When I read this book, I remember being struck by how directly it contradicted what I thought I understood about the world in which I had lived for most of my life. By that time, I had advanced degrees in both political science and United States history. My political science coursework had focused on comparative politics and international relations. But I was still very naïve about what the Cold War had meant – and more importantly, what ‘the road not taken’ might have looked like. To give you an idea of what I’m talking about, here’s the Amazon blurb about this book:

The Fifty-Year Wound is the first cohesively integrated history of the Cold War, one replete with important lessons for today. Drawing upon literature, strategy, biography, and economics -- plus an inside perspective from the intelligence community -- Derek Leebaert explores what Americans sacrificed at the same time that they achieved the longest great-power peace since Rome fell. Why did they commit so much in wealth and opportunity with so little sustained complaint? Why did the conflict drag on for decades? What did the Cold War do to the country, and how? What was lost while victory was gained? Leebaert has uncovered an astonishing array of never-published documents and information, including major revelations about American covert operations and Soviet military activities. He has found, in the shadows of one of this century's great, epic stories, the sort of details and explanations that hit with the force of a lightning bolt and will change forever the way we think about our past.

Although the Soviet Union was allied with the United States, Britain, and France during World War II, it was clear even from the outset that this alliance would not last beyond the end of the war.

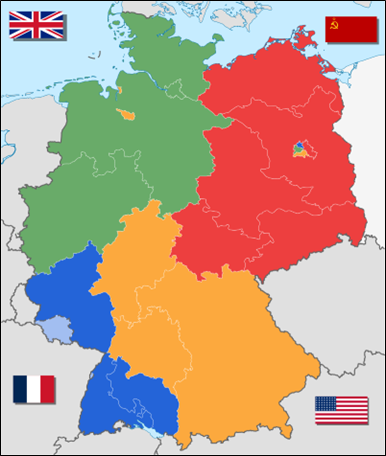

Germany and Berlin were both divided into occupation zones in April 1945. These zones remained under the control of another nation – either France, Britain, the United States, or Russia – until the establishment of West Germany in 1949.

The three Western nations soon began to work cooperatively to reestablish civil government and society in the areas they occupied. The Soviet Union not only resisted cooperation, but it actively worked to try to subvert cooperative agreements among the other three nations. From June 1948 to May 1949, Russia imposed a blockade on the sectors of Berline that were occupied by Western powers but totally surrounded by the Soviet-controlled sector. This blockade was lifted after a year, in part because the Berlin Airlift thwarted their efforts and in part because East Berlin was suffering economically along with West Berlin.

Over the next several pages, I’m going to remind you of how the world worked during the Cold War. This is brief and doesn’t cover everything that is important. But it will remind you of that world – and the current struggle between Russia and the West, as the former Soviet Union attempts to flex its superpower chops without much to back up its threats.

Containment

This policy was first enunciated by US Diplomat George F. Kennan in a 1947 article he wrote for Foreign Affairs. This was called the “X” article, because he first published it under the pseudonym “X.” Containment was a long-term, patient, but firm resistance to Russian expansionist desires. There was no effort to try to recover and reconstruct countries within the Soviet sphere of influence; instead, the goal was to prevent the Soviet Union from expanding to other places in the world. The Truman Doctrine offered aid to Greece and Turkey to keep them from falling into the hands of the Russians. The Eisenhower Doctrine supported Middle Eastern countries against communist aggression.

Alliances

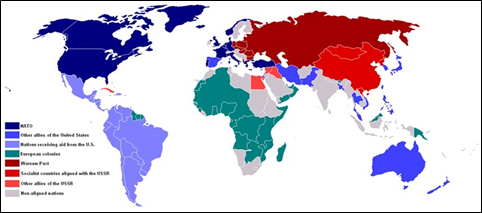

The policy of containment was achieved through a series of regional alliances (NATO, SEATO, CENTO, and the RIO Pact) during the 15 years after the end of World War II. Allies of the United States essentially surrounded – and isolated – the Soviet Union. The idea behind all of these alliances was mutual defense. This meant that an attack against one member of the alliance would be seen as an attack against all members of the alliance, and the result would be a massive – and probably catastrophic – response.

Deterrence

Political leaders and policymakers hoped and expected that the certainty of response would deter any attack. This policy of deterrence underpinned strategy during the Cold War. A possible response – from the United States, because the US was the world power whose promise was most effective – would deter anyone from attacking an alliance member in the first place.

Mutual Assured Destruction

The policy of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) was deterrence on steroids. The arguments for MAD said that if both the US and USSR developed overwhelmingly destructive weapons systems and also exhibited the willingness to use them, deterrence would be strengthened. A national leader would have to be a madman, the argument went, to unleash a military strike against a nuclear-armed nation, because the attacker’s own country would be destroyed in response. This situation became known as the Balance of Terror; so long as major military powers had the ability to obliterate their opponents (and of course bring on a retaliatory attack that would obliterate the attacking country) leaders would resist attacking one another.

Proxy Wars

Given all of this, it’s not hard to understand why Proxy Wars took the place of direct conflict between the US and USSR during the Cold War. A war directly between the world’s two major nuclear powers was too dreadful even to think about. But both countries could – and did – support proxy armies all over the world in a kind of secondary battle.

One problem with Proxy Wars is that real people from global hot spots around the world get killed and their countries get decimated so that leaders of the superpowers can avoid getting their own people killed and having their own countries reduced to rubble. This gives the World War I song Over There a different meaning: Let’s make sure the fighting occurs ‘Over There.’

There were dozens of Proxy Wars fought during the Cold War. Here are 10 of the most well-known of these. I imagine most of you remember them, although you may not have seen all of them as Proxy Wars.

Korean War (1950-1953). North Korea (backed by the USSR and China) fought against South Korea (supported by the US and UN troops). The war ended in a stalemate with the division of Korea along the 38th parallel.

Vietnam War (1955-1975). North Vietnam (supported by the Soviet Union and China) fought against South Vietnam (supported by the United States). The conflict escalated into a major proxy war, resulting in significant loss of life and political turmoil.

Afghanistan (1979–1989): Soviet forces invaded Afghanistan to support the communist government. Afghan mujahideen (backed by the U.S. and other Western countries) resisted the Soviet occupation.

Angolan Civil War (1975–2002): The MPLA (supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba) fought against UNITA (supported by the U.S. and South Africa). The conflict was fueled by Cold War rivalries and regional interests.

Nicaraguan Revolution (1978–1990): The Sandinistas (supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba) overthrew the Somoza regime. The U.S. backed the Contras in their fight against the Sandinista government.

Greek Civil War (1946–1949): Communist forces (supported by Yugoslavia and Albania) fought against the Greek government (supported by the U.S. and Britain). The conflict ended with the defeat of the communists.

Congo Crisis (1960–1965): The Congo gained independence from Belgium, leading to internal strife. Various factions, including the Soviet-backed Simba rebels, clashed for control.

Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988): Iraq (supported by the U.S. and Gulf states) invaded Iran (supported by the Soviet Union and Syria). The war had ideological and territorial dimensions.

Sino-Soviet Border Conflict (1969): Tensions between the Soviet Union and China escalated into armed clashes along their border. Both sides sought to assert dominance within the communist bloc.

Yugoslav Wars (1991–2001): The breakup of Yugoslavia led to a series of conflicts involving various ethnic groups. External powers, including the U.S. and European countries, supported different sides.

It looked as if Soviet and American forces might square off and start a shooting war in October of 1962 – the Cuban Missile that came within a whisker of starting an exchange of nuclear weapons between the two superpowers. But this didn’t happen.

After Joseph Stalin died in 1953, the leadership of the Soviet Union passed through a succession of leaders who had varying points of view about how to navigate the superpower rivalry that characterized the era. The end of the Cold War came about because Mikhail Gorbachev, a reformer, became General Secretary of the Communist Party (and thus de facto leader of the country) in 1985 and embarked on a series of reforms: glasnost (openness), perestroika (political and economic reform) and demokratizatsiya (democratization). Gorbachev thought that the only way the Soviet Union would survive was by becoming more like the Western democracies it had opposed throughout its existence. Gorbachev’s policies were adopted – at least in part – but his leadership did not survive the change.

These changes happened much more quickly than anyone anticipated. The Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989. By October 1990 – less than a year later – Germany was reunified. Thirteen months later, on December 25, 1991, Gorbachev resigned and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics dissolved.

Kirkus Reviews wrote this about The Fifty Year Wound when it came out.

There was good reason to confront the Communists, Leebaert allows: had the US not intervened in Korea in 1950, for instance, Josef Stalin “most likely would have been emboldened to crack down on Yugoslavia, the only independent Communist state in Europe.” But America’s conduct of the Cold War involved considerable betrayals (such as the abandonment of the Hungarian freedom fighters in 1956), unhappy alliances with tinhorn dictators around the world, stupid and foreseeable misadventures in places such as Vietnam, huge lies that overestimated the Soviet arsenal and the need to build up American arms to close the gap, and inexcusable gaffes in collecting and analyzing intelligence (Leebaert writes of the CIA, “no other single government body has blundered so often in so many ways integral to its designated purpose”). The author closes with a timely consideration of how such sorry artifacts of the Cold War threaten to reemerge in the new war against terrorism, led by some of the same players with much the same mindset.

It's been over 30 years since the Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union disappeared, and the world changed. George H. W. Bush, who was President when all of this began to happen, proclaimed a New World Order. In 1992, Francis Fukuyama, a professor of political science at Stanford, wrote The End of History and the Last Man, which argued that the worldwide spread of liberal democracies and free-market capitalism of the West and its lifestyle may signal the end point of humanity’s sociocultural evolution and political struggle and become the final form of human government, an assessment met with numerous and substantial criticisms. Fukuyama has since rolled back his conclusions.

Great piece. Deterrence. All for it, but these proxy wars are a horrible outcome. I would hope more countries could adopt strong diplomatic entities to deal with conflicting views. That’s my little ask for the day.