In what must have been a “holy s**t” dog-caught-the-car moment, the Second Continental Congress began to recognize that it had transitioned from protest to governance – from a loose coalition of rebelling colonies to a body that needed to assume national responsibilities. Even before independence was declared, the Congress was coming to the realization that they had to prepare, not just for war, but for nationhood. The representatives in this body could not have predicted what would happen over the next few years – and they certainly didn’t think that the Continental Congress as formed in 1774 would be the de facto government of a nation fighting for its independence for the next seven-plus years. But on this date, they decided to form committees to deal with what they saw to be the most pressing problems they faced:

Committee to Consider Rules and Regulations for the Army

Amid escalating hostilities following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Continental Congress recognized the urgent need to unify the disparate colonial militias into a cohesive fighting force. I haven’t been able to find out who served on this committee, but it’s clear that George Washington was appointed to head this committee, which was responsible for drafting the army’s rules and regulations. The efforts of this committee culminated in the adoption of the Articles of War on June 30, 1775; these articles provided a structured legal framework for the Continental Army, outlining offenses, disciplinary measures, and expectations for soldier conduct – including the importance of attending worship services. In 1776, Congress adopted a more detailed version of the Articles of War, and in 1779 Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a Prussian military officer, introduced the Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. This manual standardized training and discipline across the army and remained the official guide for the U.S. Army and state militia for decades.

Committee to Consider the Number and Pay of the Troops

Once again, I haven’t been able to find out who served on this committee. It was charged with several key responsibilities, which were finalized in a report in October of 1775:

Determining Army Size: It was agreed that the new army should consist of 20,372 men organized into 26 regiments of 728 men each (including officers, NCOs, and privates. Each regiment had eight companies, and each company had one captain, two lieutenants, one ensign, four sergeants, four corporals, two drummers or fifers, and 76 privates.

Pay Adjustments: The committee was concerned about pay disparities, recognizing that officers’ pay was too low and privates’ pay too high. They realized that reducing privates’ pay could harm morale, so they did not recommend any changes.

This committee also specified daily and weekly rations for soldiers, including the following:

1 pound of beef or ¾ pound of pork or 1 pound of salt fish per day

1 pound of bread or flour per day

3 pints of peas or beans per week

1 pint of milk per day

½ pint of rice or 1 pint of Indian meal per week

1 quart of spruce beer or cider per day

Additional provisions like candles and soap were also allocated.

Committee to Draft a Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms

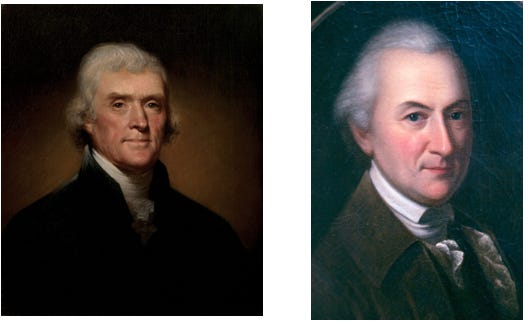

This committee was made up of seven members: Thomas Jefferson (VA), John Dickinson (PA(, Benjamin Franklin (PA), John Jay (NY), John Rutledge (SC), William Livingston (NJ), and Thomas Johnson (MD).

Initially, Thomas Jefferson was chosen to draft the Declaration due to his prior work on colonial rights. However, his draft was considered too radical by some members of Congress. Consequently, John Dickinson was brought in to revise the document, aiming for a tone that balanced assertiveness with a desire for reconciliation. The final version incorporated elements from both Jefferson's and Dickinson's drafts, reflecting a unified stance among the colonies.

Adopted on July 6, 1775, the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms outlined the colonies’ grievances against British policies, including taxation without representation, military aggression and occupation, and violation of natural rights. The declaration emphasized that the colonies did not seek independence, but were compelled to defend their liberties, saying:

"We have taken up arms in defense of the Freedom that is our Birthright... We shall lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the Aggressors."

This document served to unify the colonies, justify their actions, and communicate their position to the British Crown and to the world. It laid the groundwork for the Declaration of Independence, adopted a year later, marking a transition from seeking redress to pursuing full sovereignty.

Committee to Consider the Supply of Ammunition and Military Stores

This committee was tasked with assessing the colonies’ needs for arms, ammunition, and other military supplies. In addition to evaluating existing stockpiles of arms and ammunition across the colonies, it identified sources for procuring additional military supplies (both domestically and internationally) and recommended strategies for the production and distribution of necessary ordnance and equipment. Although specific records detailing the full membership of this committee are limited, Robert Morris, known for his financial acumen, was instrumental in organizing smuggling operations to secure gunpowder and other essential materials for the Continental Army.

As part of its work, this committee implemented several critical initiatives:

Establishing Supply Depots. In 1775, the first Continental Army Depot was established, followed by 27 other depots and arsenals to supply the army during the Revolutionary War.

Formation of the Secret Committee: On September 18, 1775, the Continental Congress created the Secret Committee, tasked with covertly obtaining military supplies and distributing them to privateers. This committee operated clandestinely, using foreign flags and intermediaries to conceal the Congress's involvement. The committee sent agents overseas to gather intelligence about British ammunition stores and to procure arms and ammunition from foreign sources.

This committee established the Continental Army's logistical framework. Its initiatives ensured that the army was better equipped to face British forces, despite the colonies' limited resources. The establishment of supply depots and the Secret Committee's covert operations exemplify the strategic measures taken to overcome supply challenges during the Revolutionary War.

Committee to Consider a Plan for Military Hospitals

The battles earlier in the year revealed the urgent need to organize medical care for the Continental Army. The committee’s primary objectives were to asses the medical needs of the Continental Army, develop a comprehensive plan for establishing military hospitals, and determine the organizational structure and staffing requirements for effective medical care.

On July 27, the Continental Congress adopted the committee’s recommendations and appointed Dr. Benjamin Church as the Director General and Chief Physician of the newly established Army Hospital. This position effectively made him the first Surgeon General of the Untied States. His responsibilities included overseeing the procurement of medicines, bedding, and other necessities. In addition, he superintended the entire hospital system and appointed key medical personnel.

The medical department was structured to manage the care of sick and wounded soldiers. The approved staffing and roles included:

Director General and Chief Physician: Overall supervision of the medical department.

Four Surgeons: Appointed by the Director General to perform surgeries and oversee patient care.

One Apothecary: Responsible for preparing and dispensing medicines.

Twenty Surgeon's Mates: Assisted surgeons and apothecaries; their number could be adjusted based on need.

One Clerk: Maintained records and managed administrative tasks.

Two Storekeepers: Managed medical supplies and equipment.

One Nurse per Ten Sick Soldiers: Provided daily care under the supervision of a matron.

This committee’s work laid the foundation for the United States Army Medical Department.

Committee to Coordinate the Postal Service

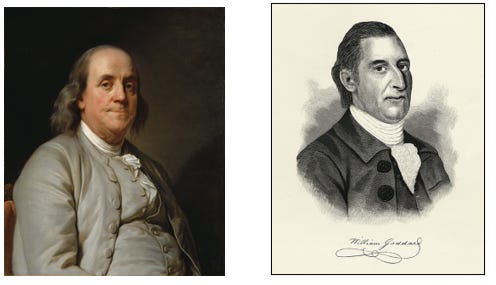

Prior to this committee's establishment, colonial communication relied heavily on the British-controlled postal system, which was both unreliable and susceptible to interception. The committee's primary objectives were to establish an independent postal system free from British oversight and ensure secure and efficient communications between the Continental Congress, military leaders, and the colonies. Benjamin Franklin was selected to lead the committee due to his prior experience as postmaster of Philadelphia and Joint Deputy Postmaster General for the British colonies from 1753 to 1774.

On July 26, 1775, the Continental Congress officially established the United States Post Office and appointed Franklin as its first Postmaster General. In this role, Franklin was responsible for organizing a postal system that spanned from New Hampshire to Georgia, appointing regional postmasters and establishing postal routes, and implementing standardized rates for mail delivery.

Franklin appointed William Goddard, a printer and publisher, as Surveyor of the Posts. In this capacity, Goddard was tasked with inspecting postal routes and offices and ensuring the efficiency and reliability of mail delivery. The success of the postal system underscored the colonies’ capacity for self-governance and infrastructure development.

Committee to Coordinate Indian Affairs

This committee was tasked with managing relations between the American colonies and Naïve American tribes during the Revolutionary War. Recognizing the strategic importance of Native alliances, the committee aimed to secure the neutrality or support of various tribes and prevent them from siding with British forces.

The committee’s objectives were three-fold: assess the disposition of Native American tribes toward the colonial cause, develop strategies to engage tribes diplomatically and secure their neutrality or alliance, and monitor (and if necessary counteract) British efforts to incite Native tribes against the colonies.

On July 12, the Continental Congress expanded its approach to establishing three regional departments – a Northern, Middle, and Southern Department – to manage Indian affairs more effectively. A notable outcome of the committee's work was the Treaty of Fort Pitt, signed on September 17, 1778, between the United States and the Lenape (Delaware) tribe. This treaty marked the first formal agreement between the U.S. and a Native American tribe, establishing a military alliance and mutual defense pact.

Overall, these committees reflected the efforts of the Continental Congress to transition from a group of colonies reacting to British policies to a unified body capable of managing a war effort and laying the groundwork for governance.

This is not to say that they solved all problems. The Continental Congress still lacked central authority, there was no mechanism for funding these initiatives, and the approach to many issues was fragmentary or incomplete. It’s fair to say that these committees laid the foundation for government, but did not go so far as creating even a framework, much less an operating system. They managed crises and provided rudimentary national coordination, but it was only in 1777 that a more formal system emerged – the Articles of Confederation (which were not ratified until 1781.)