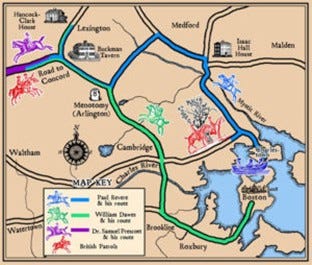

When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote Paul Revere’s Ride in 1860, he probably didn’t anticipate that it would provide the definitive historical narrative for this event – which was already 85 years back historically. He was correct that “hardly a man is now alive who remembers that famous day and year” — the “18th of April ’75” when Paul Revere rode to warn that The British Are Coming.

A couple of things get lost in this historical narrative. We don’t generally recall the last lines of Longfellow’s poem, which went like this:

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

We don’t recall that when the poem was written, America was on the verge of the Civil War over the issue of slavery. Longfellow was an abolitionist whose best friend was Charles Sumner, an activist abolitionist politician would be beaten nearly to death on the floor of the United States Senate in 1856 over his abolitionist views. The poem was published on December 20, 1860, the same day South Carolina became the first state to secede from the United States. The poem was meant to appeal to Northerners’ sense of urgency and called for action.

Longfellow has been criticized for the, shall we say, historical inaccuracies in his poem – most specifically, for his decision to eliminate other riders from the narrative. He knew about the other riders, but chose not to include them because they would have interrupted the meter of his poem. The poem became the basis for the cult that grew around Paul Revere, a previously little-known Massachusetts silversmith. When Revere died in 1818, for example, his obituary did not mention his midnight ride.

It's too bad Virginia didn’t have a poet like Longfellow. Such a figure might have written about the Powder Alarm in Williamsburg from April 20-22, 1775. On April 20, Lord Dunmore (Royal Governor of Virginia) ordered British marines to secretly remove gunpowder from the Powder Magazine and transfer it to a Royal Navy ship in the James River. He had gotten wind of growing unrest and wanted to prevent Virginia militias from arming themselves as the ones in Massachusetts had done the previous September. After that September event, British authorities began to consider ways to fend off other similar attacks, and in early 1775, Lord Dartmouth and other ministers instructed Royal Governors to secure military supplies – including gunpowder. While Dunmore claimed his action was to prevent a rumored slave insurrection, the broader pattern of British policy was clear.

When Virginians found out about Dunmore’s plan, outrage spread throughout the colony. Militia united and began to mobilize, and on April 22, Patrick Henry led a company of militiamen from Hanover County toward Williamsburg to demand that Dunmore either return the powder or pay for it. Dunmore, fearing for his safety, promised compensation and began to arm his household guard. By June of 1775, Dunmore had left Williamsburg entirely, taking refuge aboard a British warship, the HMS Fowey, moored in the Elizabeth River near modern-day Portsmouth.

Virginia may not have had a Longfellow to write a poem, but ChatGPT wrote me a poem that commemorated the Williamsburg Power Alarm. The role of Paul Revere is played, fittingly enough, by Patrick Henry.

“The Ride of Patrick Henry”

(A ballad of Virginia, April 1775)

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the ride that rang through the Tidewater clear,

When redcoats crept through the darkness deep

To steal what Virginians would never let sleep—

Powder and shot from the Magazine wall,

And sparked a rebellion from spring into fallLord Dunmore brooded with fear and pride,

For the rebel fire was spreading wide.

“Too bold these planters, too loud their cheer—

I’ll seize their powder and stoke their fear.”

So under the cloak of a midnight hour,

He summoned his marines with silent power.

Through shadowed streets they rolled the cart,

And the heart of the colony they tore apart.By dawn the whispers began to fly,

As smoke swirled up in a southern sky.

“The King has taken our stores!” they cried—

“And with them, our rights are cast aside!”

From Hanover’s fields to the James’s shore,

The farmers shouldered their arms once more.

And up from the roads came a voice like flame:

“This theft is war, and war shall it name!”’Twas Patrick Henry, fierce and tall,

Who heard the call and summoned all.

He rode not alone like Revere the bold,

But led a company strong and cold.

With rifles primed and fire in eye,

They marched on Williamsburg—do or die.

No lanterns needed, no stealthy gallop—

Just liberty’s echo and Dunmore’s wallop.To the Governor’s gates they came with will,

Demanding the powder or Dunmore’s bill.

The redcoat ruler, in pale retreat,

Felt Henry’s thunder beneath his seat.

He bargained, he blustered, he sent his gold,

But the cause of the country would not be sold.

For April’s fire, once barely a spark,

Was now a storm in the southern dark.So mark the date, and mark it well—

April twenty-second, when the stories tell

Of the day Virginia rose from sleep

To claim her soul and rise from deep.

Not with a shot, but a marching stand,

Led by a voice and a farmer’s band.

The powder was gone, but the people knew:

The fight for freedom had broken through.

Not bad for a bot.

Virginia had its own historic ride lost in history. On the night of June 3, 1781, Jack Jouett was napping behind Coo-Coo Tavern in Louisa and was woken by the arrival of British troups under Lt Col Tarleton, who were on the way to Charlottesville to capture Jefferson and members of the State Government, who had recent;y fled Richmond. Jack Jouett rode about 40 miles over back roads to sound the alarm. The legislators fled to Staunton. Jefferson, who took his time leaving for Poplar Foerest and didn't leave Montecello until the British were at the base of mountain.

Terrific! Clever and scary.