How Quickly We Forget

When I got married in 1969, one of the many things we had to think about as a couple (and a newly-created economic entity) was health insurance. At the time, I was working as a teacher (and later as an administrative employee at UVA’s School of Education) while Tim was in Law School. This meant that essential benefits like health insurance had to be provided by my employer. I don’t remember how much this coverage cost; it couldn’t have been very high, since I was only pulling down $6,000-$7,000 a year at the time.

One thing I do recall, however, was the item on the form that asked whether we wanted pregnancy coverage. That came at an extra expense, and too bad if someone was already pregnant. That was considered a pre-existing condition and thus wasn’t covered.

We didn’t plan on having children right away. We wanted to wait until after Tim finished law school – even though our plan was for me to go to graduate school once Tim was finished, this was a flexible plan that could accommodate changes in timing. As it turned out, I was pregnant when Tiim graduated in June of 1969, and I delayed graduate school for a year. We had planned this pregnancy and had appropriately expanded our health insurance coverage so that we would not have to pay for prenatal hospital care as the pregnancy moved forward. This was an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery, so I never had to think much about the limitations on coverage for unexpectedly complex medical issues.

When we began to plan to have another child a few years later, we made the same arrangements – we checked the “pregnancy coverage” box on the health insurance forms when the time came. This time, it took a year to get pregnant again, so we had to check the box twice.

A year or so after the birth of our second child, we decided that our child-bearing days were over, and we scheduled a brief non-invasive surgical procedure that pretty much guaranteed we would not have to check the pregnancy coverage box again.

I am reminded of this, of course, because the Trump administration is following a standard GOP playbook from the last 15 years – repeal and replace Obamacare (the Affordable Care Act). They have never come up with a serious plan to replace this (admittedly flawed) plan, but they want to campaign on the promise anyway, because they can’t abide anything President Obama accomplished. In a 2024 presidential debate, Trump famously said he has “concepts of a plan,” and a few weeks ago, Speaker of the House Mike Johnson said he has a “notebook full of plans.” But so far, it’s been crickets from the GOP when it comes to producing a plan that meets the healthcare needs of Americans.

I decided to look at how the ACA fundamentally changed Americans’ expectations for their health insurance. A quick look into this issue reminded me of how drastically my assumptions about health care have changed over the past 15 years.

Buying Insurance as an Individual

Before the ACA, there was no standardized retail market for health insurance. Buying insurance meant navigating a complex system of providers and insurance brokers to obtain coverage, and not always understanding exclusions or the possibility of coverage denial. Individual coverage was often unavailable, and, even when available, it was unstable and often unusable.

The ACA created structured marketplaces at the federal and state levels where individuals could compare plans through clear rules, allowing them to access standardized and predictable benefits. It became the norm to shop for insurance rather than negotiate for it.

Decoupling Insurance from Perfect Health

As I talked about earlier, prior to the ACA, insurers could deny coverage for conditions that applicants were already experiencing when they sought to buy insurance. The pre-ACA assumption was that insurers could deny coverage to people who were already suffering from challenges to their health.

Under the ACA, you no longer have to be healthy before you seek coverage. Insurance access became predictable, non-punitive, and continuous. Americans can now assume that if they lose (or change) their job, get sick, or change plans, they can still access health insurance.

Normalizing Income-Based Help

Prior to the ACA, insurance plans were often prohibitively expensive for people in low-wage jobs – which could mean anyone just starting out in the workforce, people re-entering the workforce after a period of absence, or people working in fields that do not provide high incomes.

The ACA provided sliding-scale subsidies that made middle- and working-class coverage realistic. Millions of people gained access not just to insurance but to affordable insurance.

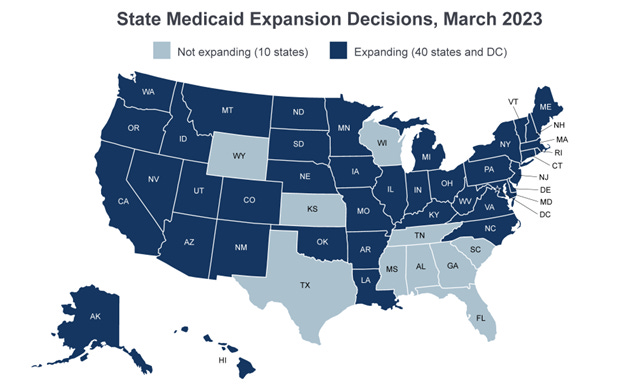

One of the most essential things the ACA did was change the perception of Medicaid from ‘emergency charity care’ to ‘first-line health insurance.’ Prior to the ACA, Medicaid was limited to narrow categories – people who were poor and disabled, pregnant women, or parents. As a result, millions of low-income adults had no access at all. Because Medicaid is a block-grant program (federal revenue is distributed as a block of funding to the states, which administer it through state mechanisms), taking full advantage of the ACA meant that states had to decide whether to expand Medicaid under the ACA. Here’s a map that shows how many states have expanded Medicaid (as of 2023).

Changes in access also reshaped early adulthood and family life. People can stay covered on their parents’ plans until age 26, offering a glide path for individuals who are still in school or working in low-wage jobs. In addition, the ACA guaranteed access after a divorce, the birth of a child, or the death of a spouse. Insurance follows people not just employment status.

I’m not going to talk about what happens in the states that have not expanded Medicaid, except to say that all non-expansion states (with the exception of Wisconsin, which provides coverage through a waiver) deny Medicaid to adults without children, regardless of their income. Uninsured rates in states without Medicaid expansion are nearly twice as high as those in expansion states (14% vs. 7%). Almost one in four uninsured adults does not receive medical treatment due to cost. Uninsured adults are also less likely to receive preventive care and treatment for major health conditions and chronic diseases. Nearly ¾ of adults in the coverage gap live in just three southern states – Texas (42% of individuals in the coverage gap), Florida (19%), and Georgia (14%).

Health Insurance is no longer employment-based

Before the ACA, when individual health insurance markets were inaccessible and unreliable, health insurance was tied to employment. The ACA didn’t eliminate employer assistance – most Americans still get their health insurance through their employer – but it changed the fallback options. People can now retire earlier, change jobs, start businesses, engage in the gig economy, or reduce their hours of employment (for caregiving, for example) without automatically losing coverage. Even people who never use the marketplace benefit from the existence of an alternative.

Big Structural Shift

Instead of asking “Can I get insurance if I’m healthy, lucky, and employed?” the ACA changes the question to “Which system do I use to get insured right now?” This can still be complicated, as there are four main access points Americans now use to get health insurance: employer, ACA marketplace, Medicaid, and Medicare, and there are flaws in the system

Paradoxically, the opposition to the ACA comes largely from the Republican Party, whose voter base is heavily dependent on the program’s provisions. This is mainly because the most direct components of the ACA are largely invisible. Medicaid expansion is usually rebranded at the state level – in Virginia, for example, it’s called Cardinal Care. People have largely forgotten (if they ever experienced) the lack of protection for pre-existing conditions and the cost of preventive care that was part of the pre-ACA environment. The low premiums associated with a subsidized marketplace have become the norm. What’s missing is a moment of recognition that says “This exists because of the ACA.”

One additional problem is that branding has become an important part of GOP opposition to the Affordable Care Act – or “Obamacare,” as they like to call it. “Obamacare” became shorthand for Barack Obama himself and for Democrats in general – the focus of GOP demonization for years. Polling has repeatedly shown that although individual provisions of the ACA are popular, the law as a whole was unpopular when named. This allowed GOP leaders to oppose the ACA rhetorically while quietly preserving its most popular elements once repeal proved politically dangerous.

In addition, federalism obscures responsibility. The ACA is structured to use states, insurers, and employers as intermediaries in the provision of healthcare. Thus, Republican governors could take ACA money while publicly denouncing the ACA. As I mentioned, state-level rebranding insulated voters from the fact that their healthcare was part of a federal program, leading voters to credit local politicians rather than Democrats in Washington.

The ACA also became a vessel for broader anxieties, as the Republican base became linked to culture war issues like economic redistribution (giving money to poor folks), immigration (giving money to brown folks), and racial preferences (giving money to black folks). Overall, the GOP has managed to cast ACA recipients as somehow “undeserving” and thus unfair to real (read “white”) Americans.

Right-leaning media consistently framed the ACA as an element of the deep state, part of a government takeover of personal decisions. It was called a threat to personal freedom and categorized as a fiscal disaster, only one step away from socialism (whatever people thought that was). They highlighted visible individual failures of the system rather than systemic gains – probably because the stories made for better television ratings.

As a result of a discussion I had with friends this afternoon, I want to add a section on how the ACA has been altered (and thus weakened) since its inception in 2010. Overall, these changes have increased the program’s cost and decreased its effectiveness.

In 2017, the individual mandate penalty was ended. The ACA originally required people to either carry health insurance or pay a tax penalty. In 2017, although it was unable to repeal the ACA, Congress reduces the penalty to zero. The mandate had been about pooling of risk. With the elimination of the penalty, healthier people chose to leave the market and insurers were left covering sicker (and thus more expensive) patients. Premiums rose to compensate.

Also in 2017, the Trump administration cut the federal ACA advertising budget by 90%. Because ACA enrollment is complicated, many buyers – first-time enrollees, older Americans, rural residents, and non-English speakers were disproportionately affected. Because enrollment was lower than projected, the smaller risk pools led to higher premiums. In addition, some areas were left with only one insurer, and the absence of competition led to increased prices.

In 2018, the federal government extended the definition of short-term plans (which are exempt from ACA consumer protections) from three months up to 12 months, and renewable for 36 months. These plans, which can exclude pre-existing conditions and refused coverage for essential health benefits, attracted healthier consumers away from ACA-compliant plans. Again, the risk pools became sicker and more expensive, leadings to increased premiums for ACA-compliant plans and surprise medical bills.

In 2017/2018, the government reduced the federal open enrollment window from 90 days to 45 days and limited access to Healthcare.gov windows during peak sign-up times. This gave consumers less time to compare plans and enroll, and was particularly harmful for people with job changes or complex family situations. This also lowered enrollment and increased premiums.

In 2018, the DOJ supported a lawsuit to strike down the ACA mandate, and, although the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the program in 2021, this uncertainty fed into increased premiums as market instability discouraged new entrants.

The American Rescue Plan (2021) provided a temporary fix to some of the problems with the ACA by increasing premium subsidies. However, this was temporary and required repeated renewals, and did not repair the structural damage done by the opposition to the program throughout its years of existence.

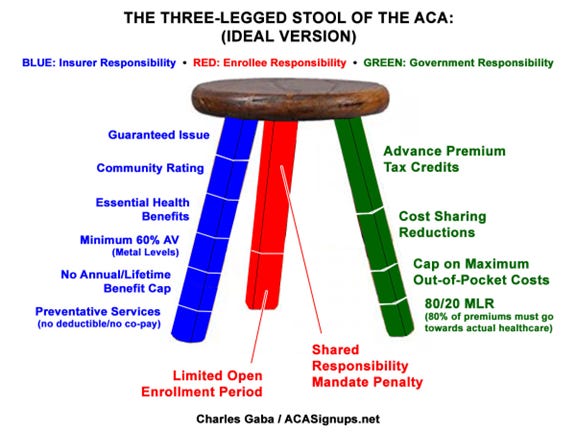

The ACA was designed as what some analysts called a three-legged stool – consumer protections, subsidies, and broad participation. From 2017 onward, federal actions systematically weakened participation, destabilized subsidies, and allowed erosion around consumer protections – raising the costs of the program without repealing the law.

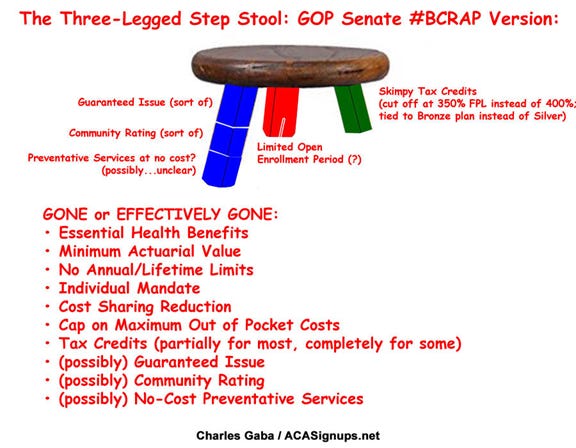

GOP efforts have continued to attack the three legs of the stool without any plan to actually build a new stool. The two diagrams below show the original plan compared to the plan supported by the GOP in 2017.

Nothing demonstrates the failures of Congress better than the ACA. The so-called "representatives" from way too many districts do nothing to REPRESENT their constituents on the issue of healthcare. Never thought I would agree with MTG on anything, but she was right on this one. Funny how it took the fact that her own children are affected by the new costs for her to change her mind - at least on part of it. I have read nothing that indicates that she is now on the side of making meaningful changes/corrections to the whole plan to make it work for everyone. Somehow we seem to have forgotten about providing for the general wellfare.

Happy Holidays to you and your faithful readers!