How Nations Fall

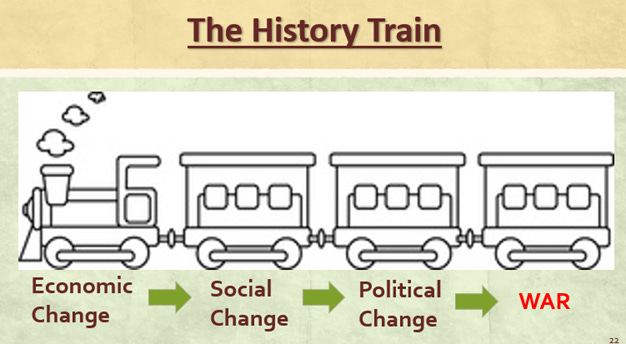

This is a graphic I like to use when I teach history classes for lifelong learning programs. It represents a theory of historical causation that goes like this.

Assumption: Economic change is the driver of history.

Economic change leads to social change.

Social change bubbles up and creates pressure on the political system to react to new challenges.

If the political system is unable to react adequately in a timely fashion, some level of violence results. The violence could be at the national or subnational level.

I came across this historical theory while I was teaching high school history and have used it ever since. Not all historians will agree with this theory, but that’s okay. Historians focus on asking questions and positing answers – not about arriving at consensus.

This fall, I’m teaching a class called Why the Civil War Happened and What We Can Learn From It. I first taught this class in 2018, during the first administration of the current Republican president. I thought there were historical parallels that modern Americans could learn from. I think that’s even more true today, and I want to spend some time this morning laying out what I mean.

Why The Civil War Happened

It’s pretty straightforward. I’m not going to spell out all of the elements I’m summarizing below.

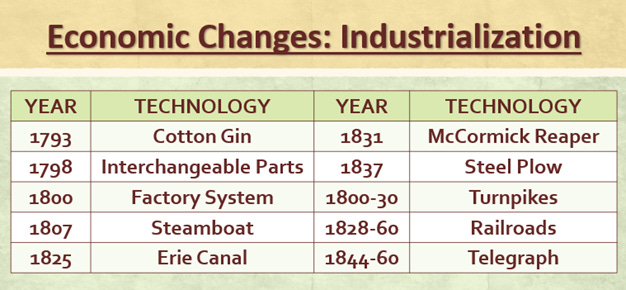

Economic changes come first.

I developed this chart to explain the major economic changes. It doesn’t take a lot of thought to realize how much things changed between the end of the American Revolution and the onset of the Civil War.

Social Changes follow:

Growth of slavery

Westward Expansion

Second Great Awakening

The Political System is forced to address new challenges:

Growing split between Industrial North and oligarchic slaveholding South.

Tariffs

National Bank

Expansion of Slavery

Territorial Expansion through treaties, annexation, and wars.

These changes were managed – although sometimes inexpertly – until the 1850s. But during that decade, the institutions of government – the ones that exist to resolve conflict – broke down.

The Presidency

Beginning in 1840, a series of ineffective one-term (or less) Presidents were elected.

1840: William Henry Harrison died in office after only one month. He was succeeded by his Vice President, John Tyler, who was defeated by James K. Polk in 1944.

1844: James K. Polk, who served only one term

1848: Zachary Taylor, who died in office after only 16 months. He was succeeded by his Vice President Millard Fillmore

1852: Franklin Pierce defeated General Winfield Scott

1856: James Buchanan defeats incumbent Pierce for the Democratic Party nomination and goes on to defeat John Fremont (from the new Republican Party) in the general election

1860: Abraham Lincoln defeated three other candidates – John C. Breckinridge, John Bell, and Stephen A. Douglas – to win the presidency while gaining only 39.7% of the popular vote

The Political Party System

Whig Party: The Whigs had emerged after the Federalist Party fell apart after 1815. Four presidents were Whigs or sorta Whigs: Harrison, Tyler, Taylor, and Fillmore. Of these four, only Harrison and Fillmore identified strongly with the party.

Democratic Party: The Democrats were split over the issue of slavery.

Republican Party: Founded in 1854 to unite anti-slavery elements in the nation, including former Whigs and Free Soilers (anti-slavery Democrats). It gained rapid support in the North and fielded its first successful candidate for President, Abraham Lincoln, six years after its formation.

Congress:

Three leaders known collectively as the Great Triumvirate – Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster – had managed sectional differences in the United States Senate since they were elected before the War of 1812. They had played a role in the Congressional effort to manage political crises over the course of almost 40 years, including negotiating the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850. All of them were dead by 1850.

In 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner was almost beaten to death on the floor of the Senate after he made a fiery speech condemning not only slavery but also the men who held slaves. South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks took extreme umbrage to Sumner’s remarks and tried to kill him. His attack was enabled by other Southern Democrats, who blocked efforts by Sumner’s allies to protect him.

Supreme Court

In the 1857 case Dred Scott vs. Sanford, Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote an opinion that contained the following language: [They] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

Not only did slaves have no rights even to bring a case to the court – Congress had never had the right to prohibit slavery anywhere. This upended all previous efforts to navigate this growing rift through legislative compromises – invalidating the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

We need to put this decision in context. The first time the Supreme Court had ruled an act of Congress unconstitutional was in 1803, with Marbury vs. Madison, which had established the Court’s power of judicial review. The second time was Dred Scott.

The States

The Compromise of 1850 and the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act had attempted to establish mechanisms for deciding how newly acquired territory would deal with the issue of slavery in their territorial constitutions (an intermediate step on the way to statehood). In Kansas, this led to a situation known to historians as “Bleeding Kansas.” The Kansas-Nebraska Act established that the people in these two territories would decide whether the state would be a “free” or “slave” state. Everyone assumed that Nebraska would be a free state – mostly because the territory was too far north to support slave-based crops like cotton. But Kansas bordered on Missouri – a slave state – so its status was less predictable.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act had neglected to indicate who, exactly, would be able to participate in this vote. So people began to pour into Kansas to participate in this vote. Two competing territorial legislatures were established in Kansas – one pro-slavery and one anti-slavery. This led to a brutal guerrilla war in Kansas between the “Free Staters” and the “Border Ruffians” – including the participation of John Brown (of Harper’s Ferry fame a few years later) and his sons in an attack on proslavery settlers near Pottawatomie Creek.

Historians highlight the events in Kansas because they led directly to the formation of the Republican Party and the caning of Charles Sumner. But Kansas was not the only state (or state wannabe) wrestling with the issue of slavery.

War Followed:

Lincoln’s victory in 1860 led seven southern states to secede virtually immediately: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Four more states — Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina — seceded after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

What We Can Learn From It

The participant evaluations for this class were overall very positive; however, one respondent noted that I had not been explicit enough about the “What We Can Learn From It” part of the course.

Frankly, I thought the connections to our situation in 2018 were pretty apparent, but I spelled them out a bit more explicitly when I taught the course again. I’m not going to spell them out this morning because you all can complete the story.

Here’s the bottom line – when the institutions of government that exist to resolve conflict systematically fail to perform their constitutional or traditional functions, violence results.

It is as true in 2025 as it was in 1860. All we have to do is look around.

Thank you Karen! A brilliant article. May I add a link to your chain? It's something you mention: technology. When I was in graduate school (seminary setting: the question was: What brings on a reformation {cousin to revolution})? I posited that technological change fosters a reformation: it was the printing press that moved Luther's teachings to the common people.. and he survived the stake burning that awaited all who criticized the religious hierarchy. Technological change brings economic possibility to many. Those who develop it ride the wave of growth yet it represents a risk to those in power. The possibility of travel drove exploration around the globe (and the shocking idea that the world was round made possible by mathematic and navigation) and colonization. Advanced weapons proved to assist oppression of native peoples. Your theory is mind bending, yet seems to be missing in the mainstream. Please keep up the good work.

Round and round we go…..