First Virginia Convention

In my Tuesday essays over the past several months I have written about events that happened throughout the American colonies in 1774 – 250 years ago. This summer, efforts to commemorate the events of that era are happening all over the country from now through July 4, 1776.

From August 1 through August 6, 1774, dozens of Virginia gentlemen assembled in Williamsburg’s Capitol Building. This in and of itself was not unusual – the colonial legislature (the House of Burgesses) had met in this room for many decades, and many of the members of that legislature were also in the room for this unscheduled midsummer meeting.

The 1930s-era reconstruction of the Capitol was based on what the Capitol looked like from 1704 until it burned in 1747. The first capitol had more comprehensive and detailed architectural documentation compared to the second capitol – including the Bodleian Plate.

This is how Wikipedia describes the Bodleian Plate:

The Bodleian Plate is so-named for its discovery in the archives of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford in England. The copperplate was bequeathed to the library as part of the collection of Richard Rawlinson, a nonjuring Church of England clergyman and antiquarian who died in April 1755. His donation to the library totaled over one million books, manuscripts, and engravings–all of which had been originally willed to the Society of Antiquaries before a falling-out.

Efforts to rebuild the Wren Building to its colonial appearance began in 1928 as part of John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s broader efforts to restore Williamsburg. The project had been in part the brainchild of W.A.R. Goodwin, the Episcopal rector of Bruton Parish. In December 1929, researcher Mary F. Goodwin located and recognized the Bodleian Plate as depicting colonial-era Williamsburg, Virginia.

The discovery proved instrumental in the reconstruction of the Wren Building–for which no other complete colonial depiction of the western side existed. Prior to the discovery of the plate, much of what renovation was planned came from descriptions written by Thomas Jefferson, an alumnus of the college. It also helped in the reconstruction of all four other structures depicted, particularly the Governor's Palace and its outbuildings.

But the meeting in August of 1774 was different from the previous meetings. For months, Virginia’s leaders had talked among themselves about how to respond to the closure of Boston Harbor and the imposition of the Coercive Acts. But this discussion was different. Instead of being held in a private home or tavern, this meeting was held in the colonial capitol – surrounded by symbols of royal authority – without the permission of that authority. During this momentous week, they organized a trade embargo, which created a model for intercolonial resistance. They also chose a slate of influential leaders to send to the First Continental Congress, which was to meet in September.

This meeting was scheduled in July so that voters would have time to select their representatives to attend it. In addition to choosing their representatives, the county meetings also passed resolutions about the conflict with Britain or instructions for the delegates to the convention.

When it met on August 1, the Williamsburg convention was in a precarious position. It lacked legal authority to legislate for the colony and faced charges of treason if it openly opposed Britain. So the representatives created a voluntary compact which they termed an “Association,” and committed themselves to a series of economic acts that would hamper British trade and thus its profits. The names of individuals who chose not to observe the embargoes, boycotts, or other restrictions could find their names published in the Virginia Gazette, with the economic consequences of boycotts extended to their own establishments.

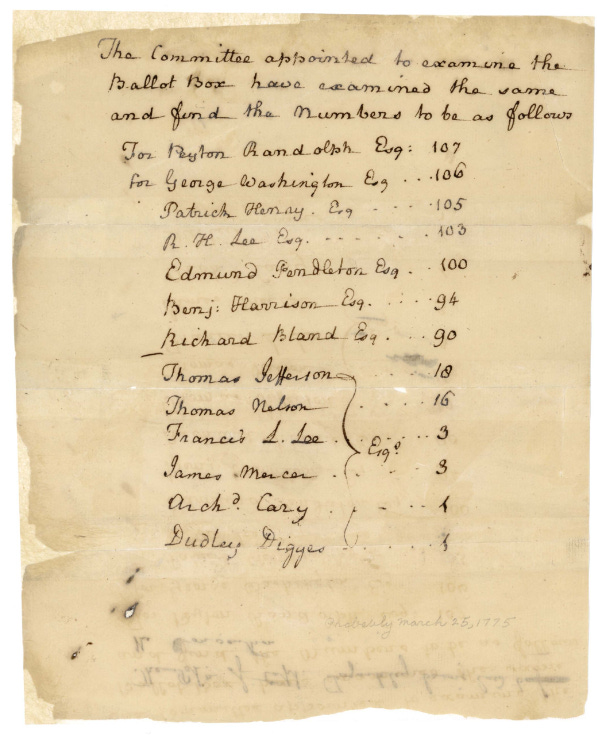

At this meeting, the delegates chose four men to represent them in Philadelphia – Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Patrick Henry, Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison, and Edmund Pendleton.

Thomas Jefferson, who was on his way to attend this meeting when he fell ill and had to return to his home, sent his notes ahead. These notes were published by the local printer, Clementina Rind, as A Summary of the Rights of British America. I wrote about this pamphlet last Tuesday.

The actions in Williamsburg during the first week of August, 1774, had ramifications across the colonies. Philadelphia revolutionary leader Charles Thomson wrote this to Virginia’s leaders: “All America look up to Virginia to take the Lead . . . You are ancient, you are respected; you are animated in the Cause.” A few weeks later, when John Adams read a report on the Virginia Association in a copy of the Virginia Gazette that he found in a coffeehouse, he wrote the following in his diary: “The Spirit of the People is prodigious. Their Resolutions are really grand.”