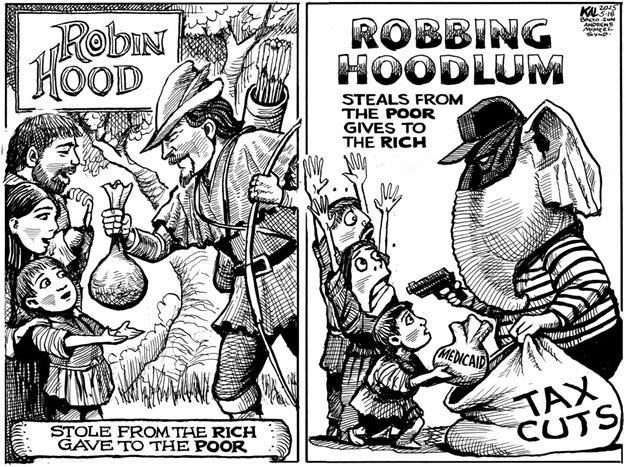

dooH niboR

The GOP is at it again. In the early morning hours of May 22, 2025 (today, as I’m writing this), GOP Speaker of the House Mike Johnson rammed the party’s Big, Beautiful, Bill through the House

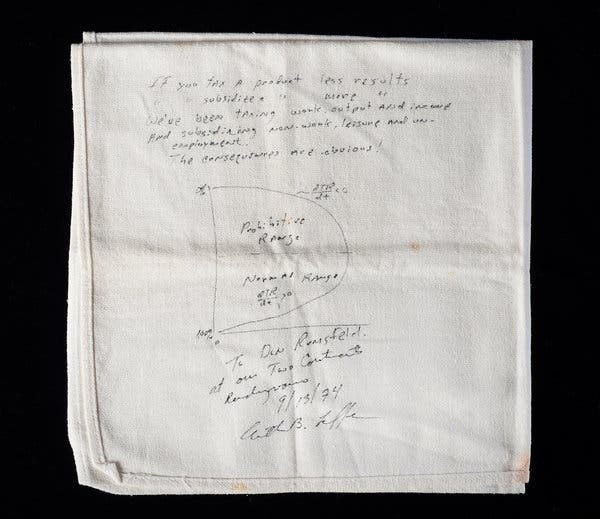

It was December 4, 1974. Economist Arthur Laffer was having dinner at Washington, D.C.’s Two Continents Restaurant with a couple of officials from the Ford Administration – including Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld – and Wall Street Journal writer Jude Wanniski. The conversation shortly got around to the economic problems plaguing the Ford Administration – problems generally summarized as “stagflation.” This problem – low economic growth (stagnation) coupled with rising prices (inflation) – wasn’t possible under the general principles of microeconomics. Yet there it was.

Although B-Movie actor Ronald Reagan was not at this dinner (really, why would he be?), this idea caught his attention as he moved toward his run for the Presidency in 1980. Newly minted as the intellectual underpinning for Supply-Side economics, the Laffer Curve became the basis for overturning Keynesian economics that had driven economic policy (not just in the United States but around the developed world) since the 1930s.

Here's a quick macro-economics summary. If you want to solve a nation’s economic problems, you can address two sides of the supply-and-demand curve: the demand side or the supply side. Keynesianism (named after British economist John Maynard Keynes, who developed the approach in his 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money) challenged the classical free-market theories that had dominated thinking until the Great Depression. Keynes’s theory sought to prove that free markets do not naturally lead to efficiency and full employment, as economists had believed ever since Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Rather, Keynes suggested that government intervention, especially through spending and taxation (fiscal policy), is necessary to stabilize a modern industrial economy.

Note: Adam Smith wrote for a pre-industrial economy. When governments (including the US) implemented his policies during the Second Industrial Revolution at the turn of the 20th century, they led to vast wealth inequality and instability, resulting in the 1929 crash.

For the next 40 years, the United States followed the precepts of Keynesian economics.

FDR’s New Deal was Keynesian – the New Deal programs were focused on putting money in the hands of Americans. Americans would then seek to spend the money, the theory went, encouraging businesses to expand. Suppliers would continue to respond to demand, the a stagnant economy would begin to expand.

During World War II, the growth of government expenditures in support of the war effort had the same effect as the New Deal programs – money in the hands of workers stimulated further economic growth.

In the 1950s, government programs (like the development of the Interstate Highway System) and tax policies (which redistributed money from the wealthy to the growing middle class) continued to stimulate demand, and the economy continued to grow.

There was a bipartisan consensus that demand-side economics was the path to prosperity. President Johnson’s Great Society was built on Keynesian principles. In 1969, President Richard Nixon stated, “I am now a Keynesian in economics.” But the energy-driven economic downturn of the 1970s – the one that ultimately led to both the election of President Carter and his subsequent defeat by President Reagan – led people to question the macroeconomic principles underlying the economic theory.

Cue the 1974 dinner.

Following the 1973 oil crisis (driven by disruptions in Middle Eastern oil supplies that resulted in gas shortages, price spikes, and long lines at gas stations), Ronald Reagan launched a bid to oust Gerald Ford as the GOP nominee in 1976. He was not successful, but he assembled a team of economists who embraced the economic principles underpinning the Laffer curve – a set of principles that were labeled “supply-side economics.” One of these advisors was Jud Wanniski, who had been at the 1974 dinner and who introduced Reagan and others to Laffer’s ideas through writings like his book The Way the World Works, which Reagan reportedly admired.

The core idea of supply-side economics is that fiscal policy should focus on the supply curve – that is, changing the economic conditions that determine what producers make and sell. The theory goes like this: reducing taxes, especially on businesses and high-income earners, spurs investment, boosts productivity, creates jobs, and ultimately leads to economic growth that benefits everyone ("trickle-down economics"). Money will still end up in the pockets of workers (who are consumers), but it will come from increased economic growth rather than through direct government subsidies.

We should recall that this has been tried several times since Reagan first proposed it in the 1980s. Reagan’s budget priorities included major tax cuts, deregulation, and increased military spending. The result was mixed: the economy grew (especially in the middle of the decade) and unemployment fell, but the federal deficit exploded and inequality increased. These problems – reflected in a weak dollar and rising interest rates – led to the 1987 Stock Market crash. In turn, these problems led to the defeat of George H. W. Bush in 1992, because as Reagan’s Vice President, he was held accountable for this economic downturn.

It was during the 1980s that Grover Norquist began to appeal to Republicans to commit in writing to his Taxpayer Protection Pledge, which asks elected officials and candidats to commit in writing to:

“Oppose any and all efforts to increase the marginal income tax rates for individuals and/or businesses, and oppose any net reduction or elimination of deductions and credits, unless matched dollar for dollar by further reducing tax rates.”

By 2010, a majority of GOP members of Congress had signed this pledge. Although the number of GOP policymakers formally committed to this pledge is hard to determine, it is clear that an aversion to raising taxes remains a prominent feature of Republican fiscal policy.

During the Clinton administration, fiscal policy was reoriented toward Keynesianism and demand-side economic policy. The economy improved, and President Clinton was able to produce a balanced federal budget during his term in office.

President George W. Bush was elected in 2000 on a commitment, in part, to return to supply-side economics. Under his guidance, Congress passed tax cuts in 2001 and 2003. The result, once again, was modest short-term growth and a strong housing market. But deficits increased, and long-term growth was weak. This set the stage for the 2008 financial crisis by favoring consumption and debt over productive investment.

During the Obama administration, several key pieces of legislation were passed to regulate banking (so that we would not see a 2008-style financial crisis again), taxes were cut, and government subsidies to healthcare once again put money in people’s pockets. This was a reversion to Keynesianism and demand-side economics.

Undeterred, the Republican candidate in 2016 vowed to cut taxes, and he did so with his 2017 tax bill, which focused mostly on reducing the corporate tax rate. The outcome was a brief GDP bump, but since most gains went to stock buybacks, not to increased productivity, debts and deficits rose significantly

Let’s cut to the chase: supply-side economics has never worked to bring about the kind of prosperity Laffer sketched out on a napkin. Each time a President has attempted to enact this kind of fiscal policy, deficits have exploded and the economy has tanked. Subsequent Democratic administrations (under Clinton, Obama, and Biden) have reverted to Keynesian principles, and the economy has recovered.

Given this history of failure, why does the GOP continue to revert to supply-side economics?

It has ideological appeal to conservatives, who generally favor smaller government and free markets. It offers a simple, intuitive narrative: “Let people keep more of their money and the economy will grow.” Politicians who already favor limited government find that this theory affirms their beliefs.

Tax cuts are politically popular and easy to sell. It’s always easier to tell voters “you’ll pay less in taxes” than to tell them “we need to raise taxes to pay for services.” In a 1984 presidential debate, Democratic challenger Walter Mondale said, “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.” Mondale was defeated by a landslide in the general election.

The appeal can be defeated, however. In the 1988 presidential campaign, despite saying “read my lips: no new taxes,” Vice President George H. W. Bush was defeated by William Jefferson Clinton.

Selective success stories enhance the appeal of the policy. Long-term negative tradeoffs don’t make good stories. Cherry-picking results helps maintain the narrative that supply-side economics “works” – just not “yet,” so we need to try harder.

Most of the wealthiest political donors stand to benefit the most from tax cuts. They fund think tanks, media outlets, and candidates who repeat supply-side talking points. As a result, even disproven claims (for example, that tax cuts pay for themselves, despite there being no evidence that this is true) remain part of the mainstream conversation.

Some politicians (particularly the well-intentioned ones who are unaware of the history of this approach) seem genuinely to believe that it will work “this time,” especially if paired with deregulation or other reforms. More often, they don’t believe that it will work economically, but they find it useful rhetorically or strategically, as a means to shrink government and constrain future spending.

The public is often confused about complex economic issues. (Ya think?) This means that any public discourse on government budgeting (including tax policy and expenditures) is muddled by a combination of well-intentioned but misinformed people and nefarious media ecosystems that traffic in disinformation in their support of supply-side orthodoxy.

In summary, politicians keep pushing supply-side economics not because it works well, but because it sells well to voters, to donors, and to aligned ideologues. It functions less as an evidence-based policy and more as a political strategy wrapped in economic rhetoric.

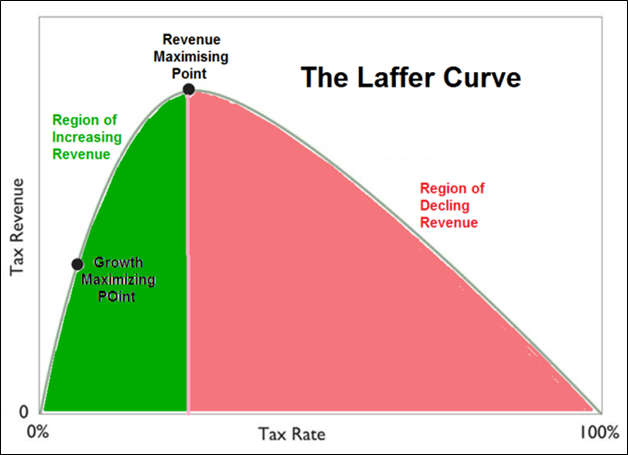

Briefly, here’s an explanation of what the Laffer curve (a supply curve) shows:

At a 0% tax rate, the government collects no revenue.

As tax rates rise from 0%, government revenue increases.

At a 100% tax rate, the government also collects no revenue because individuals have no incentive to earn taxable income. The government takes everything.

Therefore, logically, there must be an optimal tax rate (denoted as T*) somewhere between 0% and 100% that maximizes revenue.

In other words, both excessively high and excessively low tax rates lead to reduced government revenue. Maximum revenue is attained at some sweet spot – the optimal tax rate. The exact rate isn’t fixed, but rather is based on economic conditions and taxpayer behavior. Economic conditions are quantifiable but often unpredictable, in part because of conditions external to the market (global political conditions or the weather, to give two examples.) But taxpayer behavior is the real unknown – how might individuals alter their work, investment, and spending habits in response to tax changes?

In the three administrations in which supply-side economics has been attempted, neither the economic conditions nor taxpayer behavior led to the success of the policy. In May of 2025, the global and domestic economic conditions are likely going to change wildly in reaction to the current Republican party’s tariff policies and spending cuts. In addition, the uncertain economic future is going to make taxpayer behavior equally unpredictable.

In other words, supply-side economics hasn’t worked in the past and is not going to work this year. But here we are.

Well, I understand (I think) the Laffer Curve. It just seems that the sweet spot is too unpredictable and that Americans have always groused about taxes. As a result, I don’t see government having a steady/sure/predictable revenue stream with the model. Of course, I’m one of those let’s-not-starve-government people. I’m pro-government that provides services that people need. Anyway…