Democracy

Last in a series of essays on Democratic Virtues

This is the last in a series of essays on Seven Democratic Virtues – the elements of a potentially powerful vision for Democrats in the upcoming midterm elections and subsequent years. You can check these out on my Substack if you missed them or want to reread them:

November 21: Seven Democratic Virtues

November 24: Decency

November 28: Duty

December 1: Dignity

December 4: Determination

December 8: Direction

December 12: Dependability

So today’s focus is “democracy.” This is a surprisingly contentious word. We often hear people say things like “we’re not a democracy, we’re a republic,” and although this is true, it is meaningless in our current context. It wasn’t meaningless to the Founding Fathers (FFs), however. To them, democracy meant mob rule; a republic (which is nothing more or less than a representative democracy) allowed the elites to control the excesses of popular opinion. They would not have called themselves elites (well, many of them would not), but it’s easy to tell by the things they said, wrote, or did that they believed that only the proper sort – white property-owing men – should serve in government. Over the last two centuries, most democratic nations (including the United States) have expanded the definition of who should be included in this elite status.

Democracy is both a process and a condition: we achieve democracy by acting as citizens in a democracy. It seems a bit circular, because it is. The previous essays in this series tease out the characteristics of leaders demanded in a democracy. This essay will focus more on the assumptions and institutions that underpin American democracy. Specifically, I want to focus today on the Constitutional framework that established and perpetuates democracy in the United States.

Warning: This is long. I taught these concepts for a long time, so I already had the graphics. I also don’t have to look up most of the references, so that helps.

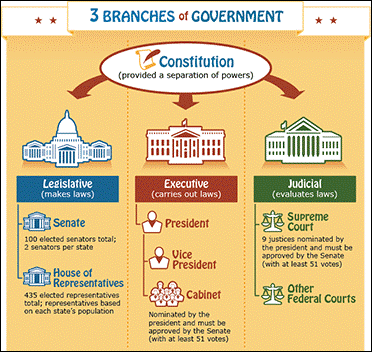

Separation of Powers

Separation of powers means that the three branches of government – legislative, executive, and judicial – are coequal. They exist on the same plane. The FFs were most concerned about how to organize and empower the legislative branch; that’s why they focused on it in Article One, that’s why it’s the longest article, and that’s why they concentrated on this article almost exclusively during the first several months of the Constitutional Convention. The Constitution addresses the executive power in Article Two, which is about half as long as Article One. One popular current theory, a Unitary Executive with expansive power, is ahistorical and dangerous. The Vanity Fair interview with Trump’s White House Chief of Staff, Susie Wiles, shows that Trump does not understand this at all – that he genuinely believes that he has the power to do literally anything he wants.

The Judiciary is addressed in just a few paragraphs in Article III; it was getting late in the convention when they turned their attention to this issue, and the Constitution says little more than that there will be a Supreme Court with a few delegated powers

and that other courts will be developed later. It was developed later — when the first Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the court structure and laid out a framework for how the federal courts would work.

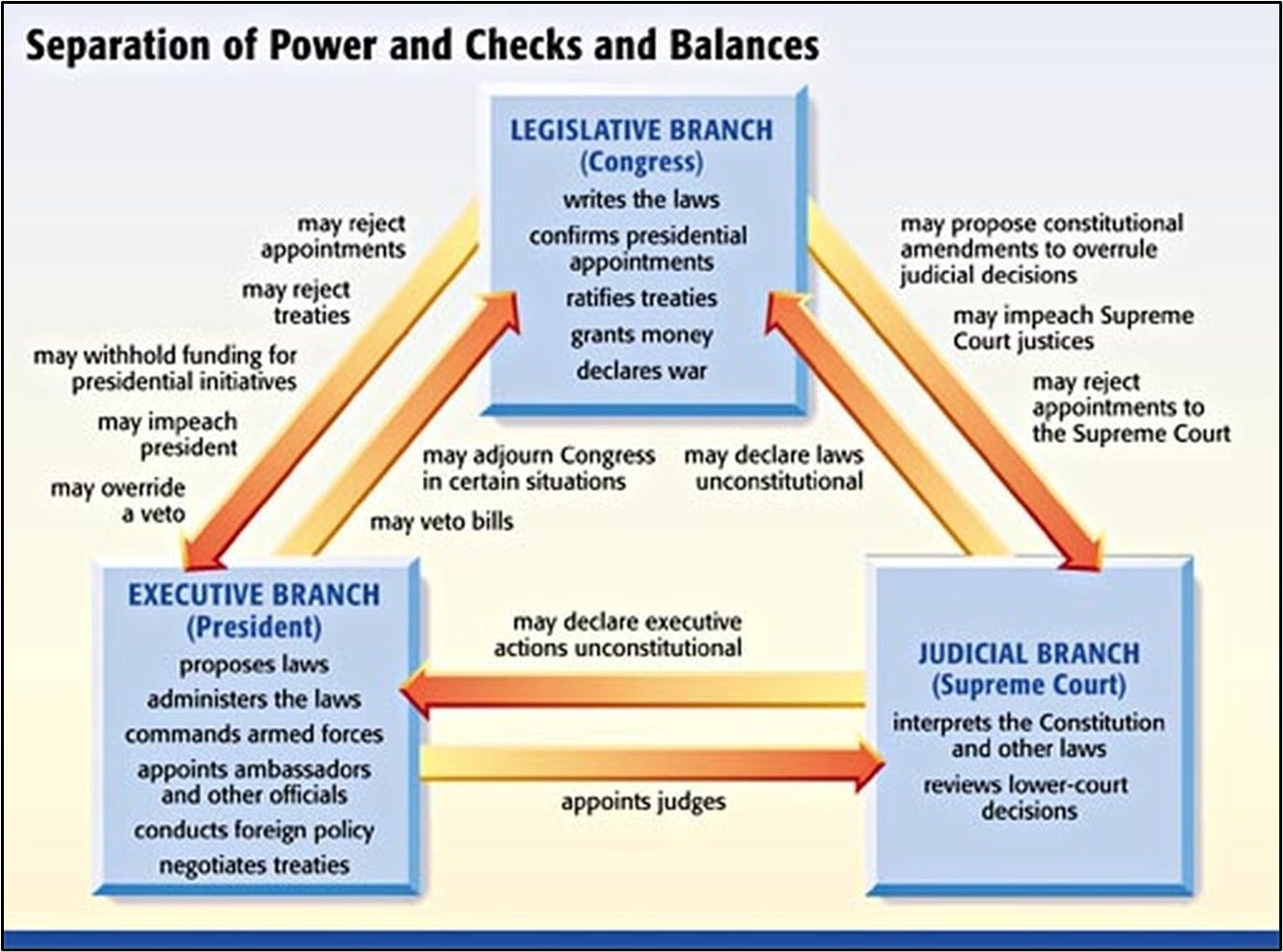

Checks and Balances

Checks and balances within the Constitutional structure ensure that if one branch attempts to do something antithetical to law, ethics, or Constitutional authority, the other branches have the tools to curtail it. We’re all familiar with the diagrams.

Federalism

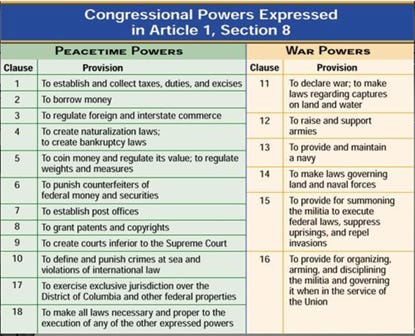

Federalism refers to the division of authority between the national and state governments. This is all set up by two parts of the Constitution – Article One, Section Eight, and the Tenth Amendment.

Article One, Section Eight, lays out the expressed powers of Congress.

The last clause in this section is often called the “necessary and proper” clause; it’s also called the “elastic clause” because it stretches the meaning of the previous clauses. Alexander Hamilton first used this provision to argue that the clauses about raising and collective taxes, borrowing money, regulating commerce, coining money, and punishing counterfeiters created the “implied” power to establish a national bank. Because 21st-century Americans are trying to use an 18th-century constitution to guide their decision-making, we have to do a lot of interpretation to make it all work. For example, Articles 12 and 13 give Congress the power to establish an Army and Navy. After World War II, Congress created and funded a third military branch – the Air Force – under this presumption of implied powers.

But it’s not so simple. The Tenth Amendment muddies the waters a bit.

This means that if the Constitution doesn’t give a specific power to the federal government, and it doesn’t forbid the states from having that power, then that power belongs to the states or to the people themselves – not to the federal government.

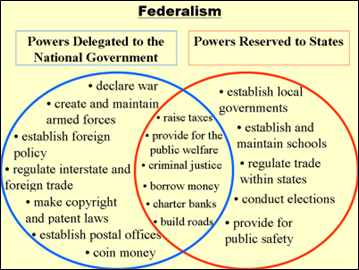

I like this chart because it recognizes a gray area – the overlapping parts of this Venn diagram.

One thing to recognize about Federalism is that it creates two separate sources of authority – dual sovereignty, in a sense – where each governing authority is sovereign in its own realm. This is where all the fights occur. There are, of course, some caveats here; Article IV of the Constitution interjects the concept of the supremacy of the Constitution and federal statutes:

This seems to contradict the division of powers I laid out earlier. The best way to understand this is that the Supremacy Clause does not give the federal government unlimited power; instead, it ensures that when the federal government acts within its constitutional authority, states cannot contradict it. The constitutional principle is that federal law binds the states, not vice versa.

Free and Independent Press

This includes freedom for investigative journalism, press access to government institutions as a restraint on corruption, and the absence of government restrictions on print or electronic propagation of information about government activities. The First Amendment to the Constitution generally establishes this:

It’s not at all clear what the FFs meant by most of this text. It depends on which FF you consult at what time in his life. Even Jefferson, almost certainly the most ardent advocate for freedom of expression among the FFs, didn’t tell us anything about how to achieve this goal.

Over the years, the Supremes have held that any government control over speech and the press must be content-neutral. In other words, if an organization follows the rules (for example, by applying for a permit for a parade or demonstration), the governing authority must apply the same standards, regardless of the demonstration's focus. The same goes for public media (print or broadcast): the government can restrict dangerous, violent, or incendiary content, but it can’t apply different standards for content it agrees with versus content it finds objectionable.

Fair and Independent Judiciary

This means that the courts are neutral arbiters, that the rule of law is emphasized more than personal loyalty, and that the power of judicial review is respected. In other words, the unelected courts often have the final authority to determine what the government can and cannot do. The Trump administration sees this as a bug rather than a feature.

Legislative bodies

These entities have to be allowed to perform their constitutional duties without interference from the other branches of government. Although the legislative process in the United States has evolved to include the President as the originator of overall budgetary strategies, the President cannot unilaterally impose his will on Congress, either by attempting to legislate by executive order or by cutting budgeted expenditures he does not personally support. These bodies also have oversight powers; once they have appropriated money for a government program, they have both the right and the responsibility to assess the program’s effectiveness. This will help them make necessary adjustments to the program in upcoming budget cycles, as well as expose any corruption or other wrongdoing in its implementation.

It is safe to assert, I think, that the current Congress has totally failed to uphold its role in this Constitutional framework. Rather than asserting its power as a coequal branch of government, the GOP-controlled Congress has totally subsumed its role to the President, acting only in accordance with the wishes of the President. This is not the framework the FFs designed.

Electoral infrastructure

The underlying structures of American elections must be secure and robust; election boards must be nonpartisan; and poll workers must be well-trained and focused on providing ballots to registered voters. One consequence of our federal system is that, because elections fall squarely within the Tenth Amendment's purview, election infrastructure varies widely across the country. This is sometimes construed negatively, as different states can adopt very different approaches to the conduct of elections and election security. However, this is also a protection against widespread fraud or interference in an election; anyone who wants to corrupt an American presidential election — even a sitting President, for example — would have to penetrate the election systems of 50 states plus the District of Columbia, along with multiple approaches within each state.

Civil Society Organizations

Citizens’ rights are protected by a variety of private organizations, including faith groups, nonprofits, unions, and a wide range of advocacy groups. These groups need to be able to access decision-makers independent of whether the lawmaker agrees with their policy preferences.

Public Education

This includes, but is not limited to, civics education in public schools. Civic awareness is fostered through public institutions such as museums, archives, and libraries, and critical thinking skills should be promoted at every level. Historical literacy is another vital component of this, as understanding what has happened in the past provides people with a context for understanding what’s happening today. Any administration that seeks to curtail what people can learn about the past, for example, degrades people’s ability to make good decisions in the present.

In addition, official pronouncements about government processes and institutions must be grounded in fact and law to avoid misleading people about what government can and should do.

Democratic Political Culture

The literature of Comparative Politics devotes considerable attention to the concept of political culture – the idea that people within a society frame their participation through a lens shaped by that nation’s history and geography. The earliest proponents of this idea of political culture were responding to the process of decolonization that swept the globe after World War II, and the emerging recognition that many countries adopted the trappings of Western democracies – constitutions, parliaments, and elections – but that these institutions functioned very differently – or collapsed altogether – across these countries.

Building on this recognition, two political scientists – Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba – wrote The Civic Culture in 1963, identifying three types of political culture, which they defined as “The distribution of patterns of orientation toward political objects among the members of a nation.” More plainly, they posited that it was essential to understand what people felt about their political system and what they felt their role was.

They came up with three types of political culture:

Parochial – people have little awareness of the political system

Subject – people are aware of the political system, but have little access to control over it

Participant – people are actively engaged and expect to be able to influence government actions.

Almond and Verba claimed that a stable democracy depends on a mix of these approaches, which they labeled “civic culture,” and that understanding a nation’s political culture could help predict the success of a democratizing process. Over the decades since they wrote, the idea of political culture is no longer used as a single, all-purpose explanation. Still, it remains influential when combined with institutions and a nation’s incentive structure – the ways people perceive avenues for success in their society.

Democratic Virtues

Almond and Verba did not tease out specific democratic virtues to support their concept of a civic culture, but I’ve done that in part through the previous essays in this series. The founders understood this as they evolved the idea of republican (small-r) virtues – by which they meant the capacity of citizens and leaders to govern themselves rather than submit to arbitrary power. Their ideals were built on the foundations of the Roman Republic, the 18th-century Enlightenment, and the English Commonwealth tradition. These foundations came together to acknowledge the necessity for self-restraint, respect for law and institutions, willingness to subordinate personal gain to the public good, and predictability and faithfulness to commitments. A republic could work, the founders believed, only if people could count on one another – on officials to keep their word, on institutions to function as promised, and on norms to restrain individual ambition. Virtue was the way to create legitimacy in the absence of hierarchy.

Democratic Processes

This piece is getting very long (ya think?), so I’m going to truncate some of this. You all know where this is going anyway.

Free and fair elections, including secure voting, easy access to voting (mail-in, early voting, accessibility accommodations like curbside voting), nonpartisan districting, and peaceful transitions of power.

Accountability mechanisms like oversight hearings, inspectors general, federal and state ethics rules, and transparency requirements

Lawmaking characterized by evidence-based policymaking, public hearings, bipartisan negotiation, and procedural regularity where the rules matter and all parties are focused on enforcing the rules rather than finding loopholes.

Public debate that protects freedom of speech, ensures truth has a platform, and encourages civic disagreement without degrading or dehumanizing political opponents.

Peaceful protest and petition is not only allowed but encouraged, as the right to dissent is fundamental to a healthy democracy. Social movements are often engines of democratic growth and renewal.

Democratic Products (what Democracy delivers)

This is where we can see if democracy is working. We pursue Democracy not just because it’s morally good – we seek it because it works. It produces things people can see, feel, and benefit from.

Legitimate Authority

Peaceful Transfer of Power

Policy Feedback and Error Correction

High-Quality Information

Public Trust and Social Cooperation

Economic Predictability and Investment

Innovation and Adaptability

Containment of Conflict

Protection against Catastrophic Abuses of Power

Durable National Cohesion

Any administration that works against these fundamental principles is operating against 238 years of Constitutional governance in the United States. Although the American brand of Almond and Verba’s civic culture is deeply embedded in the nation’s history and psyche, the Trump years have revealed how little many of us are aware of its significance or the threat Trump poses to it.

I began this series to put into words what Democratic candidates ought to lead with: a recognizable set of virtues that signal steadiness, competence, and trust. In a political environment saturated with noise and spectacle, consistent framing and demonstrated reliability are not theoretical — they are how the difference can be highlighted for voters. This emphasis on reliability and restraint is not new; it reflects the 18th-century republican (small-r) belief that a republics survive only when citizens and leaders alike can be trusted to govern themselves. That contrast has sharpened as the Republican (capital-R) Party has chosen chaos and personal loyalty over democratic norms, aligning itself with a leader whose governing instincts stand in direct opposition to the principles the Founders thought essential to a republic. This is the case Democrats should make – and keep making – in 2026, 2028, and on into the future.

This could be the most important series substack writers could create. Right on.