Counting Counts

I subscribe to economist Paul Krugman on Substack. I don’t agree with everything he writes, but he knows a lot of things I don’t know so I always learn from him.

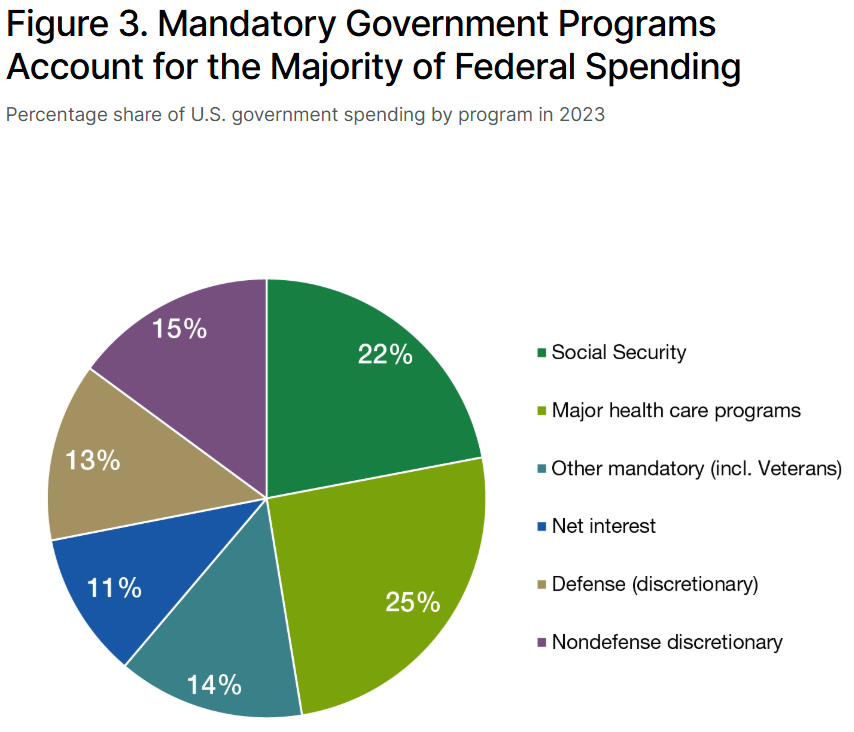

One toss-off comment he makes occasionally when talking about the federal budget is that “the United States is an insurance company with an Army.” What he means by this is that the bulk of federal spending (@75%) goes to Social Security, Healthcare, other mandatory spending including Veterans, and National Defense. We’re all familiar with charts that look like this that support his point.

I’m also currently listening to Michael Lewis’s new book, Who is Government, and in one of the chapters, John Lanchester (one of the book’s co-authors) makes the point that government has one overarching function that drives everything it does: it counts things and then makes policy based on the numbers.

Lanchester points out further that this government function is a result of classical Enlightenment thinking: that humans are rational creatures who can make good decisions if they know the situation they find themselves in – if they know the numbers.

Concerned about tax policy? You have to know the numbers. Healthcare, Social Security, Veterans’ Benefits? You have to know the numbers. And so forth.

I’m writing about this today because it has become very clear that the DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) is working in a numbers-free environment. How do we know that? One of the first things they did was fire the Inspectors General in a bunch of Cabinet departments – IGs whose job it was to count things within their agency and then make policy recommendations based on what they counted. Contrary to this, DOGE is cutting things based on vibes, so far as I can tell. I’m not going to recount the numerous “oopsies” they’ve had since they started taking a chainsaw to the federal government – they’re easy enough to find.

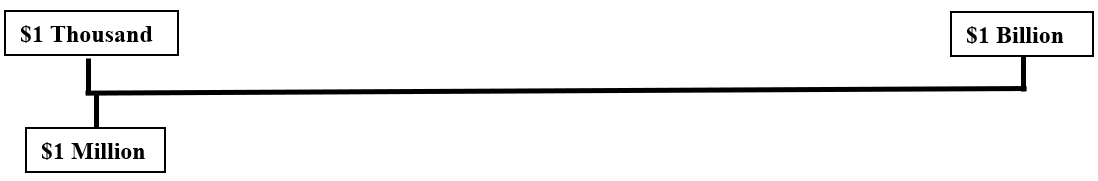

Their other errors have confused millions with billions. I recently read about an experiment done to assess people’s understanding of large numbers. In this experiment, people were asked to construct a line that had $1 thousand on one end and $1 billion on the other end. Then they were asked to place a mark at the $1 million mark; most people put the $1 million mark somewhere around halfway between $1 thousand and 1 billion mark. In reality, this is what that line would look like:

And even this isn’t really accurate – the $1 million mark should be closer to the $1 thousand mark, but you wouldn’t be able to see any difference if I tried to draw the line on this rough chart. The point is -- $1 million is a rounding error when you're talking about the billions spent in the federal budget. Budgeting discussions that can’t distinguish between a million and a billion are fundamentally unserious.

The scientific method (a product of Enlightenment thinker Sir Francis Bacon) suggests a way to go about making rational public policy:

Decide on your policy goals

Identify the data you need to know to figure out how far away your current situation is from your goal

Identify the location of the data you need

Develop a plan to collect the relevant data in a timely fashion (so that the data you collect at the end of your data collection process is in roughly the same time period as the data you collected at the beginning of your data collection process so that your data is not skewed by intervening events)

Train the data collectors so that individual preferences or habits don’t skew the data

Collect the data (a lot of work is being done by this step)

Develop processes to analyze the data you’ve collected

Analyze the data

Write your conclusions in professional language accessible to other experts so they can test all parts of your process

Distill your conclusions so they can be understood by policymakers

Further distill your conclusions so they can be understood by voters

Further distill your conclusions so they can be put on a bumper sticker

I’m kidding about the final step, but maybe not really – that can be an important part of the process of policymaking.

All of this takes time, attention to detail, and expertise. If the numbers-crunchers don’t have the numbers to crunch or are changing their counting and crunching methodology to react to the changing directives from the people above them, the numbers will not serve as any meaningful guide to policymakers.

Lanchester’s essay makes a bunch more interesting points – not the least of which is that statistics that purport to use one number to paint a picture of a complex phenomenon like the Consumer Price Index (a measure of inflation) are by definition going to differ from any one individual’s perception of what’s going on in the economy around them.

The months before the 2024 presidential election make this point. The economy was demonstrably and numerically stronger than it had been in years – and it was consistently stronger than any other industrial nation in its recovery from the COVID-19 shocks to the global economy. The official inflation rate was 3% in June of 2024 compared to June of 2023 (traditionally an acceptable inflation rate); but because the Consumer Price Index is based on a national average of a defined “basket of goods,” if people’s personal experiences – or even their anxiety about prices – were that prices were high and still rising, they labeled the economy as bad. No amount of data could overcome that, particularly with the cacophony of voices screaming that the economy was bad. Newscasters and politicians argued about the CPI, claiming that it was inaccurate or rigged in some fashion. The real process and numbers underlying the economic data were not part of the public discussion. They are complicated and boring.

If a government decides that the nation is no longer going to collect the data that should guide policymaking – or that it is going to skew or hide data so that it looks better for the people in government who are responsible for calculating and sharing the data – that nation ceases to be part of the Enlightenment Experiment. It then enters into what Lanchester labels “The Darkening.”

I don’t think we want to go there.

Yes; and in re: #5, that includes knowing who the players are in the question and what their motives are, as well as #1, what is the question, which ties in with deciding what one's goals are.

Can you tell I'm a social scientist and not an economist? Trump has no concept of what a policy is, because he has no knowledge of policy making, just dictating. Even then, he has to walk back his own dicta because he learns in front of the whole world how incompetent he is. Oh, we're there.

Me, too, but we're definitely headed in that direction.