Clara Byrd Baker

I can’t write about yesterday’s election yet. I am numb, shell-shocked, and deeply disappointed in the people who chose to vote for #P01135809 – proving that, in fact, America is NOT better than this. America is apparently precisely this, and I don’t know where I belong.

So today I’m writing about the woman for whom this school is named – Clara Byrd Baker.

Clara Olivia Byrd was born in Williamsburg in 1886. I want you to think about what it must have been like to be born a black woman in Virginia in 1886. Slavery had been abolished only two decades earlier. According to the Dictionary of Virginia Biography, her father, Charles Byrd, could neither read nor write; nonetheless, he owned his family’s house mortgage-free in 1900 and was one of only 36 African Americans in Williamsburg still registered to vote a year after the passage of the restrictive Constitution of Virginia in 1902. Her mother Malvina Carey Braxton Byrd was literate, however, and encouraged the family’s 11 children to obtain all the education they could.

Clara Byrd entered Williamsburg’s one-room public school for black children in 1892 and afterward studied privately with her instructor to prepare for the teacher’s examination. Over time, she earned her teacher’s license. She taught briefly in Williamsburg’s segregated school system before marrying William Hayes Baker, a carpenter who later became sexton (cemetery grounds-keeper) and tour guide at the historic Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg. They had four children before Clara Byrd Baker returned to teaching in 1920.

But she did something else remarkable in 1920: she was the first woman to vote in Williamsburg after the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. For the rest of her life, she was a leader in the black community of Williamsburg and in efforts to promote interracial cooperation. She helped organize a Williamsburg chapter of the National Council of Negro Women in 1958. In 1962, she was a founder of a local chapter of the League of Women Voters (to which I belong). She supported the proposed Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s. When the community gathered to pay tribute to her in 1967, the superintendent of schools declared that he could not recall a single worthwhile communitywide effort in which Baker had not participated.

For seven years after her husband’s death in 1960 she continued her volunteer work in Williamsburg while traveling extensively both in the United States and abroad. In 1967, she moved to live with her daughter’s family in Virginia Beach, where she continued her civic activism.

In 1989, the Williamsburg-James City County School System honored her posthumously when it opened the Clara Byrd Baker Elementary School near the site where she had begun her teaching career 87 years earlier

All of this information is from Cam Walker,"Clara Olivia Byrd Baker (1886–1979)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 1998 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.php?b=Baker_Clara_Byrd, accessed November 5, 2024)

Clara Byrd Baker lived to see the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s. She lived to see the (grudging) desegregation of Virginia’s public schools in the 1960s and beyond. She saw that progress can be uneven. She saw achievements and setbacks.

She lived long enough to hear Martin Luther King’s words, “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it tends toward justice.” When I decided I wanted to include this statement in today’s essay, my quick Google search about this statement revealed that Dr. King said this at Washington National Cathedral on March 31, 1968. This was his final Sunday sermon. He had been invited to give the sermon by Francis B. Sayre, Jr., the dean of Washington National Cathedral, to help lower tensions ahead of the civil rights leader’s Poor People’s Campaign, expected to kick off in D.C. in late April.

She lived long enough to hear the memorial service for Dr. King at Washington National Cathedral — on April 5, one week after the “arc of the moral universe” statement.

She lived long enough to see the delayed Poor People’s Campaign go forward in May of 1968, led by Ralph Abernathy and including the participation of Coretta Scott King.

She died before seeing Colonial Williamsburg include the stories of her ancestors in its interpretation of Williamsburg’s storied past.

Her mother’s maiden name was Braxton – the same as that of Carter Braxton, a resident or nearby King William County in Virginia, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a slaveholder. I have not been able to confirm that Clara Byrd Baker was a descendant of Carter Braxton, but I think it’s highly likely.

The Lemon Project at William and Mary (which exists to trace the descendants of the enslaved persons held by the college in the 18th and 19th centuries) recently held a symposium that brought together several Black and White descendants of Carter Braxton. So far as I can tell, this symposium did not include any mention of Malvina Carey Braxton, Clara’s mother, but I’ve emailed them this morning to find out what they know about her — if there is anything to know. I’ll tell you if I hear anything from the project.

This story reminds us of an uncomfortable truth – sometimes things are bad for a very long time before they get better, and they don’t necessarily stay better once they get better. As Mark Twain may or may not have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.”

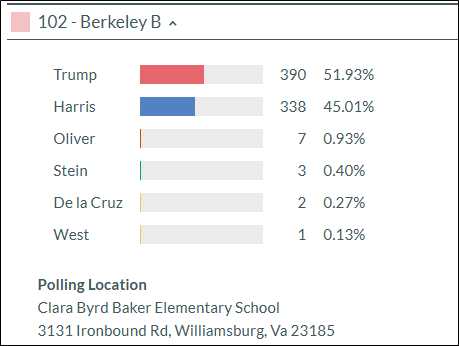

Clara Byrd Baker would have been deeply honored if she had lived to see her community name a school after her. She would have been deeply honored that the school would serve as a voting precinct. She would have been pleased that Kamala Harris – a woman of color who was denied equal access to education in her early years – carried the state of Virginia and James City County in yesterday’s election.

She would have been sad that #P01135809 won the majority of votes in the precinct that bears her name.

It is cold comfort indeed to recognize that other lots of groups have had setbacks and that some of these setbacks were more serious than this one. But I had to find something to write about this morning that didn’t make me cry.

Thank you for sharing Clara Byrd Baker today and a reminder of hope, endurance and good work by good people. A short respite from the worst-case scenarios our country—and world—are now facing.

Karen,

Do you know where that one room schoolhouse was located?

BTW, the Wmsbg Braxton family (Bobby Braxton) lives on Braxton Court within hundreds of feet of First Baptist Church on Scotland St. I’m sure he can answer your questions.

Enjoyed an Osher class with Tim today and learned we both share a friendship with Randy Boyd.