Because I was working as an election officer last Tuesday (June 17), I didn’t write my historical post as I have been on Tuesdays. So this week’s post catches us up by looking at Bunker Hill and what came next – the issuance of the first continental currency on June 22.

Things start happening pretty rapidly in the spring and summer of 1775. After the events at Lexington and Concord in April, the next significant engagement is in Boston. Although most of the action takes place on Breed’s Hill, this battle got the name Bunker Hill, and all of the historical corrections in the world won’t change the name.

This battle was one consequence of the British Siege of Boston, which began after the battles at Lexington and Concord. At the end of those battles, the colonial militias forced the British to retreat to Boston, where they were trapped by the surrounding militiamen. This began the Siege of Boston, which impelled provincial congresses in several colonies to begin calling up troops and coordinating support for Massachusetts. The Americans were concerned that the British might try to break out and seize the high ground around the city, particularly Charlestown Peninsula and Dorchester Heights. To preempt this, colonial forces decided to fortify Breed’s Hill, which overlooked Boston and the harbor.

On June 17, British forces launched a frontal assault on Breed’s Hill. Although the British ultimately took the ground after three attacks, they suffered heavy casualties (around 1,000), far more than the Americans.

I have a genealogical connection to this battle – my 6th great-grandfather, Parley Brown, fought in this battle alongside his brother, John Brown. Parley was 38 years old and his brother was 42. I have read several accounts of their participation in this battle; none of them have official documentation, but they reflect the story that was told by the participants themselves. The red circle on the map shows where their unit was deployed during the battle. It’s a simple story: John was injured in one of the British attacks, and Parley pulled him from the battlefield rather than leave as he was ordered. John survived until 1821; Parley died a little over a year later at the Battle of White Plains.

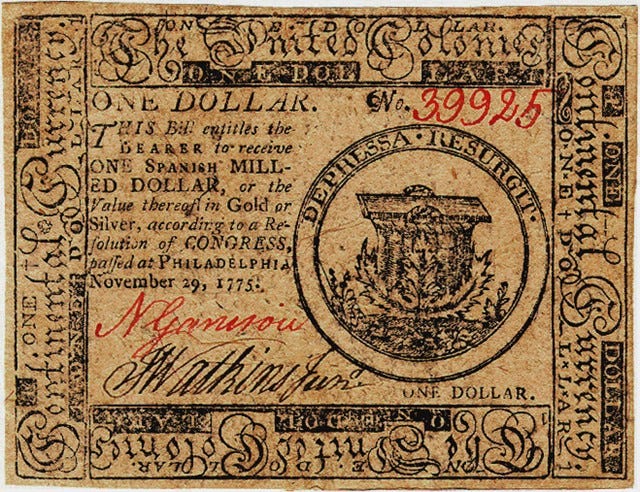

On June 22 (just a week after the battle), the Continental Congress authorized the issue of $2 million in bills of credit. Bills of credit are another term for paper money – promises of future repayment by the government. Since Congress had no authority to tax (and thus no guaranteed revenue), these notes were backed only by the trust and future success of the Continental Congress. Because the Congress had just authorized the creation of the Continental Army and appointed Washington as commander, this money was meant to pay soldiers, buy arms and supplies, and support logistics for the siege of Boston and other military campaigns.

Congress apportioned responsibility for repaying the notes among the colonies according to a formula based on population and wealth. Each colony was expected to levy taxes later to redeem the bills, although compliance varied. This led to future difficulties as the continued issuance of paper money (the Continental) led to their depreciation and resultant inflation.

This was a symbolic and practical assertion of independence, more than a year before the Declaration of Independence in July of 1776. It asserted economic sovereignty and tied the fates of the colonies together and thus was an important step toward nation-building.

Great piece. Great map. Comparing the map in your post to a map of the area today amplifies the remarkable faith colonists had in their work to create a country based on freedom. It’s just dumb luck that I was born here to live the life I’ve had. This is what happens when you get old. You reflect on the luck you’ve had and the decisions you’ve made to experience the privileges you have.