A Primer on War

A Bonus Stack

I never served in the military. I am not a military strategist. I do have some experience in studying the political context of war – both the causes and consequences.

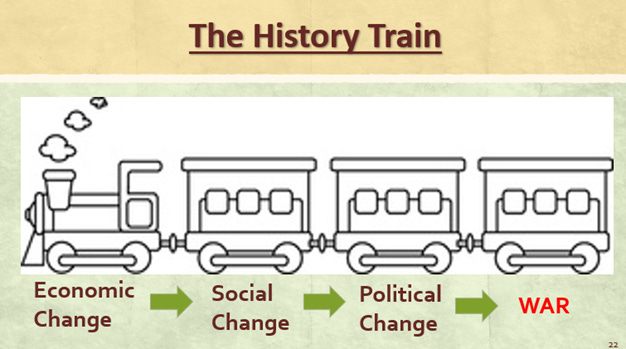

I developed this slide while I was teaching high school, and I still use it regularly in the history and politics courses I teach for the Osher program at William and Mary. I like this model of historical causation because of its simplicity.

Here’s how it goes:

The premise of this historical model is that economic change is the driver of history. This includes technological change – anything that changes the relationship among the factors of production, which are land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. Not every historian agrees with me, but that’s okay. Historians don’t always agree with each other. Think about things like the cotton gin, the railroad, telegraph, telephone, light bulb, internal combustion engine, automobile, radio, airplane, television, computer, laptop, cell phone, artificial intelligence to see what I’m talking about.

These economic changes cause social changes – changes in the way people live in society. You can think about the social changes caused by the economic changes I mentioned above. All of these changed the ways people lived, ate, travelled, worked, vacationed, gained an education, and communicated.

Social changes challenge the norms of society. When these challenges become disorderly, the government steps in to try to re-impose order. The government passes legislation that either re-establishes or alters the status quo to accommodate the social changes. Think of various efforts to provide and then regulate the services made possible by the social changes we’ve looked at in this essay.

If the political system is unable (or unwilling) to provide room for the social changes created by the economic changes, some level of violence may result. This could involve labor strikes, street violence, or warfare at the subnational or international level.

All of this is a way to say that wars do not cause themselves. They are the product of stressors to established norms (either domestic or international) that cannot be resolved through the political or diplomatic process. Wars are fought to achieve political ends.

I’m thinking about this today because the leaders of the United States are once again considering getting involved in a war in the Middle East. This time it would be to help Israel destroy Iran, but the rationale for this potential involvement is, shall we say, a bit unclear. Depending on the time of day or who the current Republican president talked to most recently, the United States may or may not drop bunker-buster munitions on Iranian nuclear facilities with the goal of either bringing about regime change in Iran or not bringing about this change or some other goal altogether that no one has enunciated yet because they haven’t thought of it.

As I said at the beginning of this essay, I’m not a military strategist. But I have read a lot that has been written by military strategists, and one of the things they consistently stress is that no nation should go to war unless they have a good sense of what they want to achieve through warfare. They should be able to describe the post-bellum world at some level of specificity. Another way of saying this is to ask the question, “How will we know if we won?”

If we look back through history, we can see that successful wars started with the winning side having a pretty good idea of what they were fighting for.

American Revolution: Americans were fighting for independence and the treaty that ended the war granted that status.

American Civil War: The North was fighting to maintain the Union and the end of the war required the secessionist states to rejoin the Union.

World War I: The Allied Powers sought to defeat the Central Powers – Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire to end their threat to European stability and balance of power. The treaty that ended disarmed Germany and dissolved Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.

World War II: The Allied Powers sought to defeat the Axis Powers – Germany, Italy, and Japan – and shape the postwar world order to prevent future conflict. This war was ended through a series of military occupations, peace treaties, and new international institutions that sought to address the weaknesses of the status quo ante bellum.

Subsequent wars have not been as successful as these earlier efforts, primarily because the wars began without a consensus among the nation’s leaders about what they wanted the situation to look like after the war – what victory would look like. The problem, I suggest, is that these later wars were fought in part to defeat an ideology rather than a specific nation. There is no one who can either surrender or claim victory for an ideology, so the postwar settlement will inevitably be uncertain and unsatisfying.

Korean War: This war began as a holdover from post World War II occupation regimes. The Soviet Union and the United States – allies during World War II – occupied Korea after World War II, dividing the country along the 38th parallel and accepting the surrender of Japanese forces in their respective zones in the North and South. The division, which was intended to be temporary to allow for the disarming of Japanese forces and stabilizing the peninsula, soon solidified as Cold War tensions between the occupying powers prevented unification. In 1948 two separate states were established, and in June of 1950, North Korean forces invaded South Korean across the 38th parallel. We know that this war ended without a resolution of the basic conflict between the two global superpowers, culminating in an armistice but not a formal peace treaty.

The goals of the United States shifted during the war. Overall, the goal was to stop the spread of communism and protect South Korea’s independence. Later, the U.S. expanded its goal to include the reunification of Korea under a democratic government; but after Chinese intervention and a long stalemate, the U.S. goals reverted to restoring the defending the 38th parallel.

American leaders did not have a clear goal for what the situation in the region would be after the war, but I think it’s safe to say that they would not have predicted that the division of the Korean peninsula would continue for 70 years.

Vietnam War: This war began with a rationale similar to that of the Korean War: the containment of communism in Southeast Asia, in a county that was divided between a communist North and a non-communist South. But unlike in Korea, there was no clear battle line in Vietnam. Instead, the guerilla warfare broke out across South Vietnam, as the communist-led forces (both from North Vietnam and from within South Vietnam) engaged American forces in unconventional warfare. Many of you are old enough to remember the wildly divergent goals various American leaders enunciated during this war – from winning over the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people to “bombing them back to the Stone Age.” And of course there’s the “we had to destroy the village to save it.”

Unlike in Korea, the United States was not able to maintain a presence in the country but rather let it fall to the forces of the North. We all have heard some military leaders claim that the military did not lose this war – that the American politicians were to blame. Militarily, they are probably right. But wars are fought for political reasons, and the United States lost the political will to fight – mainly because the nation lost sight of what we were fighting for.

Iraq and Afghanistan: These wars were both fought in part over ideology – defeating radical Islam. This focus came about because of a number of factors, but I think the main one was the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Since the end of World War II, American foreign, diplomatic, and military policy was based on a negative – the defeat of communism – but there was no unifying positive goal describing what that might look like. If you look around the world during the 50 years of the Cold War, the main determinant of which countries the United States supported was which side the Soviet Union was backing. The United States took the other side. That process provided no unifying positive principal, and was thus a shaky basis for foreign policy once the Soviet Union was gone.

I remember seeing a magazine cover in the early 1990s that featured a picture of a Muslim religious leader; the accompanying story was that the Islam would be the new communism – that the United States would structure its foreign policy around the notion that Islam was the greatest threat to global stability, and that American foreign policy would be focused on defeating this ideology. The 1992 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and subsequent regional conflict solidified this concern, and the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, relegated any other regional or ideological conflict to a lesser status. We were all in – on Iraq and Afghanistan.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were fought largely outside of public scrutiny. They involved a relatively small number of soldiers, and military operations in dusty backwater nations didn’t garner much public attention. These conflicts were part of a broad U.S. strategy known as the Global War on Terror. Other than the broad goal of defeating Islamic terrorism, little explanation was provided about what the status quo post-bellum would look like. Would these be secular westernized countries? Would they still be democratic Islamic nations? There was no public-facing explanation of what the goals would be, except, once again, in the negative. Iraq had to have a new regime (hopefully a democratic one) and wouldn’t be allowed to have weapons of mass destruction. In Afghanistan we wanted to get rid of al-Qaeda, remove the Taliban from power, and establish a stable democracy in the country. But the way we fought these wars did little to achieve a stable status quo post bellum. Instead, in each country, efforts to promote democracy collapsed after the United States left, terrorist forces returned (ISIS and Taliban), and regional stability deteriorated. The United States lost these wars by any meaningful definition.

I’m writing about this today, of course, because the current Republican president seems to be on the verge of joining Israel in its aerial campaign against Iran. But there seems to be little agreement on the goal of this engagement – what would it mean to win? Destroying Iran’s nuclear weapons capability? Killing the current leader of Iran? Toppling the Iranian government and establishing a democratic regime? Inflicting enough harm on the Iranian people that they topple their own government? Once again, depending on the time of day and the most recent person to have talked to the current Republican President, it could be any, all, or none of these.

Just to make the point one more time. Wars are fought for political reasons. If political leaders choose to engage in war, they need to have a clear view of what they’re fighting for, and the people of the country have to buy into the explanation. That’s how democracies work.

An excellent essay, Karen. Thank you.