250 Years Ago: The Death of Deborah Read Franklin

At first glance, this brief announcement doesn’t tell us much. Of course, we’ve heard of Benjamin Franklin, and we know he was married, although most of us would not recognize Deborah’s name. I taught an Osher class on Benjamin Franklin a few years ago and discovered a lot about her. She deserves our attention and respect.

Deborah Read was born in 1708, probably in Birmingham, England, to Quaker parents who came to Philadelphia in 1711. According to Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, she first met Benjamin in 1723, when he arrived in Philadelphia and walked down the street carrying “three great puffy rolls.”

Benjamin was born in Boston in 1706 to a father of limited financial circumstances. He was indentured to his brother, James, in 1718. James was a printer who soon came into conflict with the important Mather family in Boston. When he was imprisoned, he released Benjamin from his indenture so he could run the business until James was released. Instead of running his brother’s printing business, Benjamin skedaddled to New York and then Philadelphia, arriving penniless and homeless in Philadelphia in 1723 at the age of 17.

He rented a room in the Read family home, and, when Deborah’s father died in 1724, Benjamin proposed marriage to Deborah. Deborah’s mother refused, and Benjamin was hired by a Philadelphia printer, Samuel Keimer, as an apprentice. Later that year Keimer sent Franklin to London to purchase printing supplies, but Franklin was left stranded there when the promised financial support fell through.

Franklin wrote to Deborah while he was in London and appeared to be in no hurry to return to Philadelphia. Deborah married a man named John Rogers in 1725, but things went badly. He may have already been married, and he soon took off for parts unknown. Word filtered back to Philadelphia that Rogers had died, but there was no proof. When Benjamin returned to Philadelphia, he and Deborah decided to get married, but she couldn’t marry unless she could prove that she was a widow. The penalty for bigamy was serious – life imprisonment.

In 1730, Benjamin and Deborah entered into a common-law marriage. This meant that they simply had to announce that they intended to live as husband and wife, and that’s what they did. This situation was propelled by the fact that Benjamin had a son, William, that year – but not by Deborah. In one of the best-kept secrets of American history, the identity of William’s mother has never been revealed. Deborah entered into the common-law agreement with Benjamin and agreed to raise William.

Benjamin and Deborah had a son, Francis Folger Franklin (known as Franky) in 1732, but he died of smallpox in 1736. They had one more child, Sarah (Sally), in 1743. She married Richard Bache, and they had eight children; one of their children, Benjamin Franklin Bache (Benny) became a favorite of his grandfather and accompanied him to France when he served as the American representative there during the American Revolution.

As Benjamin developed his printing and other business interests in the 1730s and 1740s, Deborah played an important hands-on managerial role. As Benjamin’s fame grew, he came to spend less and less time at home, leaving Deborah in charge for years at a time. He was out of the country for the better part of 28 years between 1757 and 1775.

1757-1762 He was the representative of the Pennsylvania colony in London for five years

1764-1775 After two years back in Philadelphia, he returned to London in 1764.

1775 He returned to Philadelphia – six months after Deborah’s death

He and Deborah wrote regularly while he was away – mostly about business affairs and the decisions Deborah was making. She was unwilling to travel and felt (probably correctly) that she would not fit in with the London society that Benjamin was enjoying. The standard biographies of Benjamin portray Deborah as ignorant or provincial. More recent scholarship, however, shows her to be an adept, although modest, Philadelphia socialite who served as the country’s assistant postmistress, a gracious hostess for the most important people in Philadelphia, and a savvy businesswoman. Their letters reflect her desire for him to come home and his promises that he will do so – sometime soon.

Meanwhile, Benjamin had essentially recreated his home environment in London. While Deborah and her daughter Sally were running the business and household in Philadelphia, Benjamin was living in the home of Mrs. Margaret Stevenson and her daughter Mary (or Polly) not far from Westminster. Margaret was born in 1706 – the same year as Deborah – and Polly was born in 1739 – three years before Sally. There is no indication of a sexual dalliance between Benjamin and Margaret, although Polly was a regular visitor when Benjamin was in Paris during the American Revolution.

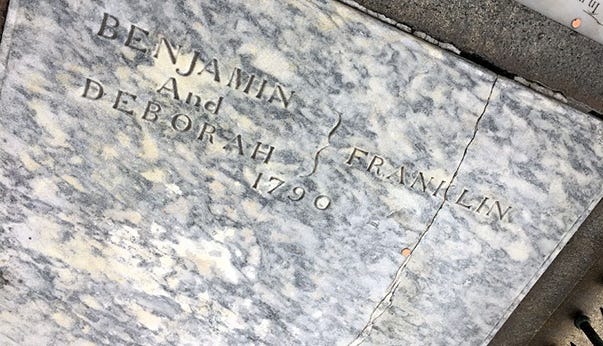

Deborah had a stroke in 1769 and her pleas for Benjamin to return became more fervent. He continued to promise to return ‘sometime soon.’ Deborah died after her second stroke in 1774, not having seen Benjamin for ten years. Benjamin did return to Philadelphia in 1775 – but not because of Deborah’s death. He left London because he had suffered humiliation in Parliament as a result of his changing views on the struggle between Great Britain and her North American colonies. He had been a firm believer in Britain’s right to tax her colonies in the 1760s and thought that the current unpleasantness would be resolved. By 1775, however, he had been converted to the American side in this conflict and went back to Philadelphia to play a role in the events there.

This 2023 book puts a different spin on Benjamin Franklin and the women in his life, with 2/3 of the book devoted to Deborah. I just came across this book in the last few days and I haven’t read it yet – it came out after I taught my class on Benjamin Franklin. I’ve requested it from my library and I’ll read it later this week. I’m looking forward to knowing more about Deborah.